Issue #4: A Head Above the Rest: Whole-Roasted Cauliflower with Labne

Reluctant to Blanch, Recipes for Cauliflower and Labne, a Pita Tease, plus More about Me

Welcome back to Kitchen Sense, my new newsletter of recipes, cooking advice, and thoughts about food. I hope you enjoy it. If you do, please share the link with your family, friends, and fellow cooks. If this is your first issue, you missed the best apricot jam in the world, seasonal asparagus with miso butter, and double chocolate chip muffins. Most of the content is available to those who sign up for free. Paid subscribers are able to access the entire archive at any time, leave comments, and ask me directly for recipes and cooking advice. They will also occasionally receive a bonus recipe or two. (This weekend they got my recipe for the best blueberry muffins ever.) Happy cooking.

Roasting a whole cauliflower is probably nothing new. One imagines that as long as there has been cauliflower—which some botanical historians date to the 12th century—cooks have been roasting whole heads of it in high heat. I know enough about culinary history to know that you can almost never be sure who made what first where. But these days, whole-roasted cauliflower has come to be associated with cooks in Israel, especially Eyal Shani, who roasts truckloads of cauliflower to stuff in pita at his ever-expanding empire of Miznon restaurants, which in addition to the original in Tel Aviv, now has outposts in Paris, Vienna, Melbourne, and New York. Whole-roasted cauliflower has become a signature dish. (For my thoughts on signature dishes, including the power structure that such assertions of ownership reinforce, see my foreword to Phaidon’s recent anthology Signature Dishes that Matter.)

Although Israeli food has become a global trend, the term and the recipes are understandably fraught with the complex politics of that region. Cultural appropriation is just the starting point. The recent escalation has made the topic of Israeli food even hotter, not in the trend sense, but in the produce-a-spark-and-it-will-explode sense. Questions of oppression, colonization, social and racial justice, cultural value and appropriation—in short, power—are topics I hope to make readers of this newsletter think about in the context of recipes and home cooking, which is my focus. For far too long, food writing, especially recipe writing, has avoided addressing complex issues that might interfere with the “fun!” and “celebration!,” not to mention the digestion, of the meal. But such omission at the expense of those without the agency and political clout to share equally in the joy and the reward is problematic for me, as it should be for you. As a secular, progressive American Jew who is still grappling with his relationship to the history and the politics of Israel—where I’ve met some amazing people, toured some amazing places, and enjoyed some delicious things—I believe we all must work to end oppression and disenfranchisement anywhere and everywhere, however best we can. Food offers us an opportunity, a challenge to do so.

The first time I ate a whole-roasted cauliflower was, in fact, in Israel in 2009—two years before Shani opened his first Miznon—at an unforgettably fabulous lunch prepared by the iconic Israeli chef and provocateur Erez Komarofsky at his hilltop home in the Galilee surrounded by a beautiful garden. (You can read about that meal in an article I wrote for Art of Eating.) Komarofsky had roasted the large heads of cauliflower in his wood-burning oven—he used no electricity to prepare that lunch for us—and served them in a puddle of tahini drizzled with silan (date syrup). I had another delicious whole-roasted cauliflower the following year at Domenica in New Orleans, where chef Alon Shaya, also Israeli, snuck a few Middle Eastern accents onto the otherwise Italian menu. Like many, I have eaten whole-roasted cauliflower at Miznon. It’s easy to see how it’s become associated with the Israeli kitchen.

Without access to a wood-burning oven myself, for years I’ve roasted whole cauliflower from its raw state in an ordinary gas oven preheated to 450°F. I oiled up the head, seasoned it with plenty of salt, and roasted it in a cast-iron pan, all in an attempt to recreate the intense heat of a wood-burning oven. Honestly, I was never happy with the result. Sometimes it came out beautiful and browned, but it was never tender all the way through, not even after two or three hours of roasting. And sometimes it came out shriveled and burnt and still tough. I’d been advised that the best thing to do was to blanch the cauliflower in boiling water first, but I brushed that off as too troublesome. It felt like cheating.

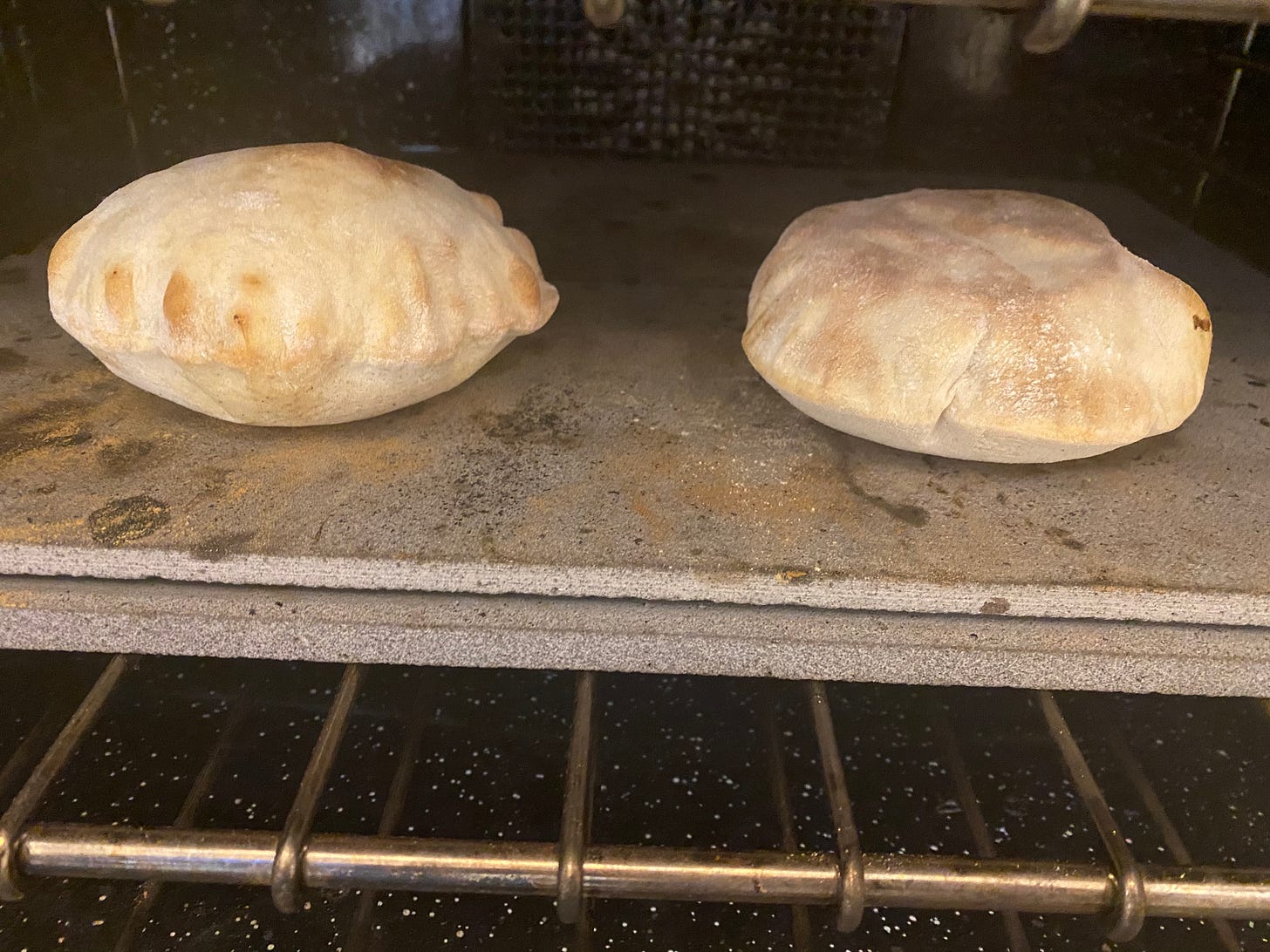

I was wrong. Frustrated with my tough, time-consuming cauliflower, I finally gave in and blanched one before roasting it. Not only did blanching cut the cooking time by more than half, it produced the darkly browned, tender cauliflower I was looking for (see photo, above).

To save even more time (and water), to make the whole endeavor a little less cumbersome, and to produce a less water-logged result, now I steam the cauliflower for about 5 minutes (a little more for larger heads, less for smaller ones) before roasting it. This sets me up for a perfectly roasted, browned cauliflower that’s easy to cut (and even easier to eat) in less than an hour.

For the home cook, the hardest part of this process is removing the steamed cauliflower from its pot without damaging it. (And it isn’t that hard.) The florets shouldn’t be so soft that just touching them with tongs leaves a mark. But it can still be difficult to navigate the whole thing out of the pot in one piece. If you let it cool completely before removing it, the cauliflower will overcook. A steamer insert is a real help, as it gives you some leverage. Some large tongs or two large metal spoons are also helpful. Whatever you choose to do, be sure to have a receptacle for the cooked cauliflower nearby in case you lose your grip. This can be a plate or tray, or else the baking sheet or cast-iron pan you are going to roast it on.

I serve whole-roasted cauliflower many ways, but my favorite has become room temperature in a pool of seasoned labne. In fact, the picture above was one of the most popular photos I’ve ever posted on Instagram. Sometimes I add a sprinkle of sumac or zaatar or a drizzle of pomegranate molasses or silan. I let guests carve the cauliflower into chunks at the table, spooning the labne on top of their portion. Nothing could be more delicious and refreshing on a hot summer’s day.

Labne(h) Learnings

Labne or labneh is a type of fresh “cheese” made for millennia in the Levant by straining cultured milk (i.e., yogurt) to make a thick, creamy spread. (I use quotation marks because it really isn’t a cheese in the technical sense of the term.) Across the Middle East, labne is eaten and used many ways, one of my favorite of which is as a meze simply seasoned with garlic and salt and drizzled with olive oil to scoop up with warm pita. I also love it with roasted cauliflower. As with tahini, which is the name used for the plain sesame paste as well as the lemony-garlicky sauce made from it, labne is the name of the fresh cheese as well as the seasoned meze made with it.

I recall an informative lunch with friends years ago at a hotel in Dubai where they had a meze buffet that showcased selections from different Arab countries—Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and Syria among them. Although each array of appetizers was similar—hummus, labne, falafel, moutabal, muhummara—the opportunity to compare regional variations was exciting. I recall the labne being similar from one to the next. (I’ll note that I have no idea how accurately these variations were represented, but I appreciated the attempt to debunk our reductive categorization of all “Middle Eastern” cuisine as the same. See future commentary on “Chinese Food.”)

I’m fortunate to live a few blocks from Kalustyan’s, where I can always buy a good quality labne (and just about anything else)—thick, creamy, and tart. (Further to my comment above about the variation among mezes, at Kalustyan’s you can also find many similar-but-different ingredients from different parts of the world that show the subtle variations between spices, grains, condiments, what have you that, we tend to elide into a global melting pot. #culinarydiversity) Labne lasts a long time, so I usually have some at the back of my fridge. When I don’t, I make it or approximate it in a variety of ways. The simplest and most common way is to use full-fat Greek-style yogurt. Fage is my brand of choice for this because it is already quite thick and it has a decent tang, something not easy to find among American yogurts. You can strain it further if you like, but you don’t have to. Sometimes I’ll stir in some sour cream to add richness. In a pinch, I will combine sour cream and yogurt or even whipped heavy cream and buttermilk to approximate the texture and flavor of labne. Experiment for yourself.

RECIPE: Whole-Roasted Cauliflower with Labne

1 medium head cauliflower, 6 or 7 inches in diameter, weighing between 1 ½ and 2 pounds

Extra-virgin olive oil

Sea salt

Black pepper

2 cups plain labne or alternative (see above)

1 medium clove garlic, peeled

Fresh lemon juice

Zaatar, sumac, pomegranate molasses, silan (date honey), pomegranate seeds, chopped cilantro, extra-virgin olive oil, alone or in combination (optional)

Preheat the oven to 450°F. Have a cast-iron pan or parchment-lined baking sheet at the ready.

Trim the cauliflower, removing the leaves by using a long-ish paring knife to cut around the core. I don’t mind if a few small, pale green leaves stay attached. If the core extends beyond the florets, trim away some of it so that it recedes about a ½ into the center of the head. With the tip of your knife, poke an x in the center of the core.

Find a pot with a cover just large enough to hold the cauliflower and still be covered tightly. Add about ¾ inch of water to the bottom of the pot. If you have a steamer insert place it inside the pot. If you don’t have an insert, you can still cook the cauliflower this way, but it may be trickier to remove from the pot when it’s done (see advice, above). When the water comes to a boil, add the whole head, right side up, being careful not to damage it or splash yourself with hot water. Cover the pot, turn down the heat, and steam for 5 minutes. This should be enough to jump-start the roasting. Turn off the burner, remove the lid, and careful remove the steamed cauliflower to its roasting pan

Drizzle the steamed cauliflower generously with olive oil, rubbing it into the head with one hand. It will disappear into the florets. Sprinkle with salt, also generously. Finally add a sprinkling of black pepper. Set the cauliflower in the preheated oven and roast for 35 to 45 minutes, turning the pan once or twice, until the head is deeply and evenly browned.

While the cauliflower is roasting, prepare the labne. Using a Microplane grater, grate the garlic clove into the labne. Add a pinch of salt, some black pepper, and a tablespoon or so of olive oil. Stir to blend well and set aside. If you don’t have a Microplane, I’d suggest you use a mortar and pestle and a pinch of salt to pound the garlic into a paste. As a last resort, chop it with a knife, mixing with some salt, and pressing it against the board with the knife blade as you work, to produce a paste.

When nicely browned (see photos), remove the cauliflower from the oven. You can serve it hot, but I prefer to make it in advance and serve it at room temperature, especially on a hot summer day, when you want the oven’s heat to dissipate before anyone sits down to dinner.

Spoon about half of the labne onto a serving plate, and with the back of the spoon, spread it out unevenly to cover the surface. Carefully place the roasted cauliflower on the labne. Add a squirt of fresh lemon juice and whatever garnish you might be using. Serve the remaining labne on the side. I present the cauliflower with a knife and a spoon so people can cut themselves hunks of cauliflower and scoop the labne on top. Mmmm.

More About Me

Who is Kitchen Sense? I’ve been cooking seriously since I was a little kid—for more than 45 years. I am the youngest of four siblings in a family that liked to eat. I worked in a butcher shop during my sophomore year of high school in Toronto and I started a catering and soup company before I graduated. (Btw, no one in Toronto would ever say “sophomore year”; it was Grade 11, the second of four high-school grades; we went to Grade 13 back then.) We never had much money—my father died when I was nine and my mother was disabled and didn’t work—but eating well and entertaining were always important at home. My mother had a limited repertoire, but she was a very good cook. I went to hotel school on scholarship and worked in restaurant kitchens to support myself. I lived, studied, and cooked in France during college and in Italy after, returning to the U.S. and New York City in 1992 to write about food, chefs, and restaurants any way I could.

After a couple of years as editor-in-chief of the hardcover quarterly Art Culinaire, I joined the James Beard Foundation, where I remained for almost 30 years. During that period America’s food, restaurant, and celebrity chef culture was coming into its own—for better and for worse. While at JBF, I completed a Ph.D. in food studies at NYU, wrote or co-wrote five cookbooks (the most comprehensive of which was called Kitchen Sense, hence my social media moniker), and had the opportunity to eat my way around the world, learning about different food and food cultures along the way. I’m not mentioning any of this to impress. I just want to underscore that food has occupied my thoughts, day and night, for my entire sentient life. I used to describe myself as monocultural, food being the only cultural pursuit that I interested me. (My horizons are broader now.)

I believe it is not just practical but imperative, maybe even spiritually beneficial, to know how to cook. Cooking connects you to the past, keeps you focused in the present, and gives you security for the future. I believe we need to be more aware of where our food comes from, whose hands have touched it before ours. And I think we have to work hard to provide access to and education about good food so that everyone can eat healthfully and wholesomely. In 2017 epicurious.com named me one of the "100 Greatest Home Cooks of All Time." You can find out more about me and my professional background on the website for my consulting company Kitchen Sense, LLC and on my Linked In profile. And for previews of what’s to come in this newsletter and other cooking advice (plus the occasional post about our Bernedoodle puppy, Milo) be sure to follow @kitchensense on Instagram and Twitter.