Issue #112: Raspberry Jam Session

The Easiest Jam You Can Make

As parts of the world experience record-breaking heat, while other parts experience record-breaking flooding, and still other parts experience record-breaking hail, not to mention the tornado that hit Milan, I encourage you to recall that as much as 25% of the human impact on climate is the result of how we grow, distribute, cook, consume, and dispose of our food. Be mindful about what you eat and make better choices for yourself and the planet. Jam made from local, seasonal fruit is good idea. Thanks for your support—Mitchell

For me, few things are more gratifying than making jam.

Enjoying a spoonful of jam in the dead of winter made from fruit you preserved in the heat of summer is about more than just its delicious taste. There’s something that connects you to the cooks who came before, before we expected fresh raspberries to be available all year round.

Even more gratifying? Making jam from fruit you grow.

Last year, the plum tree on our terrace and the calamondin citrus tree in our living room both fruited for the first time in the three years since we brought them into our home. I had enough fruit to make about a ½ cup of plum jam and a whole cup of calamondin marmalade and you’d think I had climbed Everest. This year the plum tree is heavy with fruit—the result, it would seem, of Nate’s hand pollination of the blossoms. If it all matures, watch out….

Picking fruit and making jam is also a blast.

Sunday Nate and went raspberry picking at Indian Creek Farm, a lovely u-pick place less than five minutes from the house we are renting on Cayuga Lake. Even though the raspberry canes were already quite picked over, we came up with two quarts of beautiful fruit in no time. Later, at the impressive Ithaca Farmers Market, one of my favorite berry sellers had beautiful golden raspberries and black raspberries on offer for only $5 a pint. The latter are a specialty of the region. Mitchell’s jam factory has been open this week.

Jam Session

Although I regularly make all kinds of jams—apricot-vanilla jam in the style of Alsatian jammer Christine Ferber was the subject of my first Kitchen Sense newsletter—I was struck by how easy raspberry jam is to get right. Unlike other fruits that have to be pitted, peeled, or otherwise prepped, or those that are low in pectin, that mysterious, finicky polysaccharide that baffles but gives jam its distinct textural jaminess, raspberries almost always do what they are supposed to, and fast.

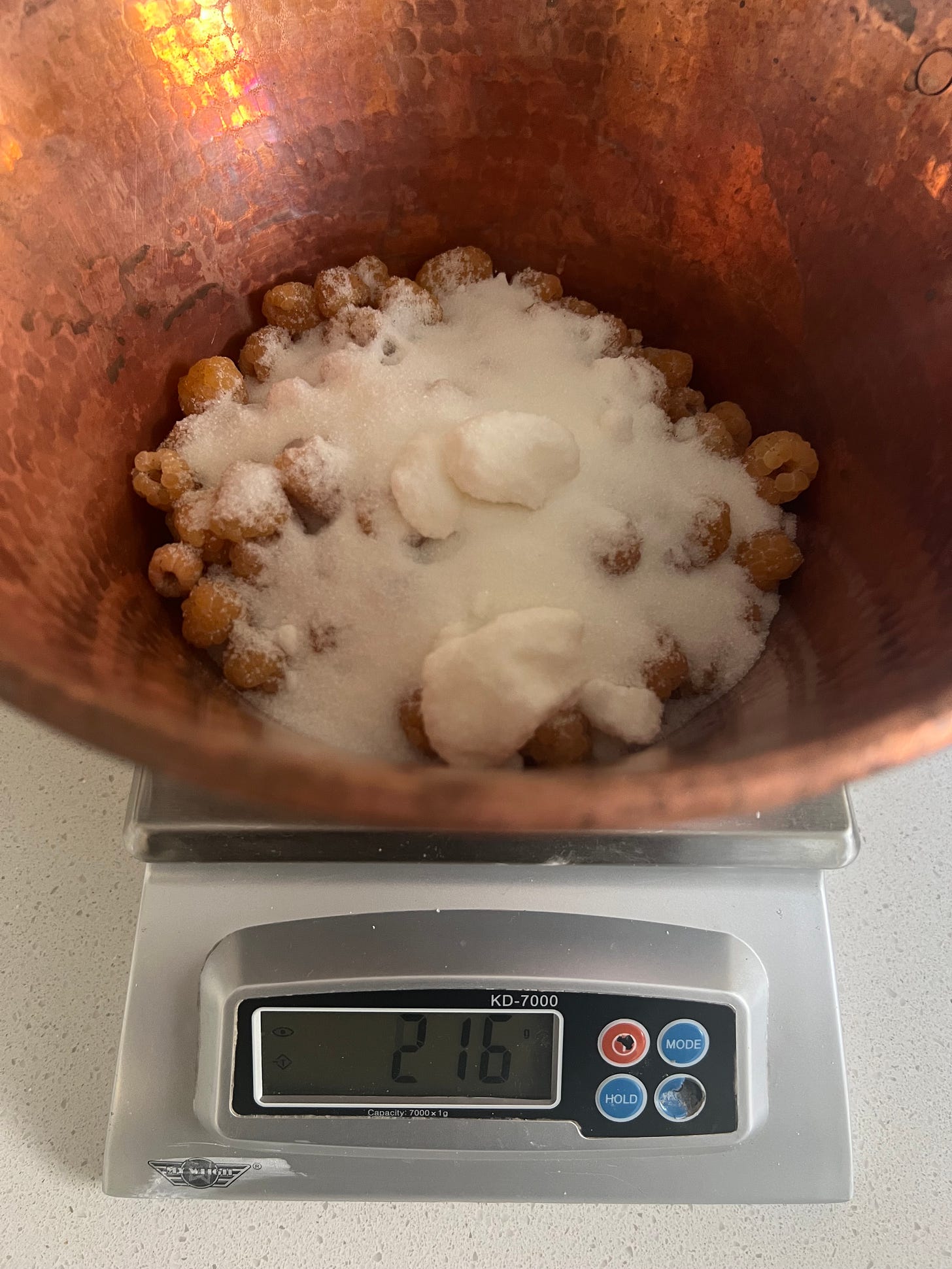

Ferber recommends not even washing the berries to preserve their aroma. (She also prefers you grow them yourself.) Instead, she picks them over to remove any leaves and stems and dumps them directly into the jam pot, where they are combined with sugar (80% of the weight of the fruit) and a squirt of fresh lemon juice. A quick boil, some stirring, some simmering, and in 5 to 7 minutes you have a perfect raspberry jam. C’est tout!

If you are close watcher of the Great British Bake Off, which I am, you will note that raspberry is virtually the only jam they make on set for the same reasons I want to encourage you to give it a try: it is quick and nearly foolproof.

Three processes contribute to the final consistency of any jam: evaporation, caramelization, and pectin development. To encourage evaporation of any excess water in the fruit, jam is usually made in a wide pot with plenty of head space for it to boil up and foam. If your pot is too small you will be sorry and your stove will become a sticky mess.

For the caramelization effect, similar to candy making, you need the sugar to attain a certain temperature, usually around 221°F, so it thickens when it cools, but not too much, or it will become a sticky, tacky sludge. This is a common mistake of new jam makers because you have to stop the cooking before it reaches the right texture. It will thicken considerably when it cools. But stop it too soon and it won’t thicken at all.

Pectin is the last piece and I call it mysterious and finicky because I’m not sure anyone really understands it. The cells of the fruit contain a polysaccharide that is released and forms pectin when the fruit is cooked with sugar in the presence of acid. The less ripe the fruit, generally, the more pectin it has because ripening is in part a process by which certain starches in the fruit convert to sugar. Still, some fruits have very little pectin, no matter their degree of ripeness, such as strawberries and cherries. These are harder to jam without the addition of extra pectin, a perfectly acceptable approach to jam making that for some inexplicable, purist, pioneer-spirit reason I try to avoid. Citrus fruits and apples are very high in pectin, and in fact, they are often used to make the pectin you add into other fruit jams.

But here’s the thing about raspberry jam making. You don’t really need to know any of this. My experience with raspberries is that if you get the proportions right, they jam up in minutes. You can grow, pick or purchase your fruit, in season or out. You can use a fancy copper jam pot on a wood-burning fire. Or you can use a glass bowl in the microwave. You can make a large batch or teacup’s worth. You can preserve it for long-term storage in sterilized jars using the water bath technique (here’s a decent demonstration). Or you can just keep it in a container in the fridge until it is gone.

So, I offer you the recipe I used four times just yesterday to turn all of those multicolored raspberries into jam. The yield depends on the amount of fruit you have. A packed pint (250 to 300g) of raspberries will produce approximately 1 ½ cups of jam, while a quart will make twice as much (duh). Just keep the ratio of 80% sugar to fruit by weight. The color of your raspberries doesn’t matter. I hope you give it a try.

An important warning. Never put a spoon you have eaten from back into the jam jar. This type of cross contamination is what causes most jam to spoil. If you are diligent about using a clean spoon every time, your jam will last a very long time.

RECIPE: Mitchell’s Raspberry Jam

(Makes about 3 cups)

500 g (about 1 quart) fresh raspberries, picked over to remove any leaves or stems but not washed

400 g (about 2 cups) granulated sugar

Juice of ½ lemon

Clean a couple of containers to hold about 2 cups of jam. No need to sterilize them if you aren’t going to process them in a water bath for long-term storage. If you are, look online for how-to advice.

In a wide, heavy-bottomed saucepan, combine the berries, sugar, and lemon. Together the ingredients should stop less than halfway up the sides of the pot. The jam will boil and froth more than twice its volume. You’ll be sorry if it boils over.

Set the pan over medium high heat and stir to combine as the mixture begins to melt together. As the fruit heats, the berries will break down and the sugar will dissolve. Keep stirring. When the mixture begins to boil, it will increase in volume. Modulate the heat to maintain a steady simmer and stir occasionally until the jam begins to thicken. You can tell it is thickening because the froth will subside somewhat and the bubbles will slow down. It also begins to make a jammy sound, which I know sounds crazy, but it does. Watch and listen to the video below. Keep stirring.

The whole process should take about 5 to 7 minutes, no more. While still on the heat, you definitely do not want it to have the texture of a finished jam, which will mean you have overcooked it. But it also should not be totally liquid, either. In my opinion, it is better err on the side of too loose than too firm because you will almost always want to go too far, especially if this is the first time you are making jam.

Most recipes will tell you to skim the froth from the surface of the jam while it cooks. Since the entire thing seems to be froth to me and I never know what to take or what to leave, I do not skim my raspberry jam. Once it is done, I give the jam one last stir and let it sit for a minute or two. Everything seems to settle and the froth seems to disappear completely, so I don’t know what the point of skimming is, to be honest. Maybe I’ll never win the jam award at the state fair.

Transfer the finished jam to the clean container(s) and enjoy, now or sometime in the winter.

One Final Note: Seedless

If you, like my proofreader Carol, hate seeds in your raspberry jam, you can remove them. But since the seeds are key to the development of pectin, you shouldn’t strain them at the beginning. Instead, cook the jam about halfway, until the fruit has broken down, the sugar has dissolved, and the jam has boiled for a couple of minutes. Pass through a mesh strain, not too fine, and return to the pot. Bring back to a simmer to allow the evaporation and caramelization to take place.