Issue #115: Marinated Zucchini with Basil and Mint

How Italians Marinate Vegetables "Like Carp," "Like Laundry," and Other Delicious Memories

Can it really be mid August? —Mitchell

When I was an apprentice cook at a small restaurant in Torino, Ristorante Balbo, back in 1992, the chef/owner, Luigi Caputo, kept a jar of marinated vegetables on the windowsill. Although Luigi hailed from Puglia, the restaurant specialized in traditional Piemontese food—Barolo-braised beef shank known as stincho al cucchiaio, an elaborate finanziera stew made with cock’s combs and spinal marrow, lamb-filled agnolotti del plin, and in season, egg-yolk-rich tajarin pasta smothered in white truffles. But that jar of zucchini or eggplant in carpione, “in the style of carp,” as it is called in Piemonte, captivated me.

We ate la famiglia, the staff meal, every night at 7 pm. (The restaurant opened at 8 pm.) Our dinner often reflected Luigi’s southern roots. He’d bake black-olive rolls (watch out for the pits!) and toss pasta in spicy tomato sauce. I’d often help myself to a pile of the sharp, garlicky, melanzane or zucchine in carpione on my way from the kitchen into the dining room. Sandwiched in one of those warm olive rolls, it was one of the culinary highlights of my time there.

As I was flipping through the pages of Leah Koenig’s new Portico cookbook, which explores the cuisine of the Roman Jews, I came across a recipe for marinated zucchini that reminded me of those pickled vegetables in Luigi’s window. Fried in olive oil, layered with a mixture of chopped fresh basil, mint, and garlic, and doused with vinegar, the dish is known in Rome as concia, which Leah tells us derives from an old Roman term for hanging laundry to dry in the sun, a reference to the drying of the zucchini that is how the recipe begins.

Concia di zucchine is part of a wide variety of marinated, pickled dishes, sott’aceti (or “things under vinegar”), that are popular throughout Italy. In addition to the carpione of Piemonte, there’s the scapece of Naples, from the Spanish escabeche. In Venice I think of sarde in saor, fried sardines and onions marinated in vinegar with raisins and pine nuts, which likely also have Jewish roots. No doubt vinegar was prevalent in many dishes because it acted as a preservative before refrigeration.

Jews have lived in Rome for more than 2,000 years and their influence on the cuisine of that city’s iconic cuisine cannot be underestimated. Leah’s book captures the spirit of the community and their recipes so well. Her work is also a testament to the reality that, despite how hard we might look, there really is no such thing as a unified “Jewish cuisine,” beyond the notion of “food Jews cook.” Having lived among various cultures for so long, Jewish communities around the world cook food that more closely resembles the food of their neighbors than it does the food of each other. (For more on this and other Jewish food subjects, listen to my interview with Leah on my What’s Burning podcast here and subscribe to her substack, The Jewish Table, here.)

The day Leah’s book arrived I set out the make her concia. I already had a few Romanesque zucchini in my fridge. These light-green, ridged zucchini have a meatier texture and more pronounced flavor than the more common, smooth, dark-green zucchini we usually find in U.S. markets, though Leah assures us both work fine. I sliced them lengthwise about ¼-inch thick and let them dry between paper towels, as suggested. Then I fried the slices in olive oil, sprinkled them with the herb-garlic mixture, and doused them with vinegar to marinate.

The marinated slabs of zucchini were delicious. We ate them with fried chicken for dinner that night. But they had a slightly different texture than Luigi’s zucchini as I remembered it. (I’ll note, his was likely Piemontese-Pugliese, not Roman Jewish—world’s apart.) Also, the frying took some time and made a bit of a mess of my kitchen, oil splattering all over the stove despite having left the zucchini to dry in paper towels for several hours. So, the next day I made a slight adaptation to the original recipe, slicing the zucchini very thinly on a mandolin, brushing the slices with olive oil, and broiling them for a few minutes until browned before marinating. The results were also delicious, and more like the texture I recalled.

Since I liked both results, I offer you both variations. The thicker, fried slices make a great side dish or sandwich stuffer. The thinner, broiled slices make more of a condiment. Both capture the essence of the best Italian food: a few fresh, seasonal ingredients that come together in a delicious synergy. And since zucchini and basil are very much in season this minute, you should make one or both versions asap.

RECIPE: Marinated Zucchini with Basil and Mint

Adapted from Portico

(Serves 6 to 10, depending on what you do with it)

About 2 ½ pounds zucchini, the smaller the better, but any will do

A generous handful of fresh basil leaves, finely chopped (a heaping ¼ cup)

A generous handful of fresh mint leaves, finely chopped (a heaping ¼ cup)

1 large clove garlic, minced

About ¼ cup red wine vinegar

1/3 to 1/2 cup extra-virgin olive oil

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

To make Leah’s version with thicker slabs of marinated zucchini, slice the zucchini lengthwise or crosswise ¼-inch thick. Line a sheet pan with paper towel. Arrange the slices in single layers between sheets of paper towel on top of each other. Place a second pan on top and let them sit at room temperature to dry for at least an hour, or longer.

In a small bowl, mix together the chopped basil, mint, and garlic, and set aside. Have the vinegar ready. (I just use it straight from the bottle.) And you’ll want some sort of non-reactive, rectangular baking dish nearby to layer and marinate the zucchini.

Heat a large frying pan over medium-high heat and coat the bottom of the pan with a thin film of olive oil, about 1/8-inch thick. Fry the dried slices of zucchini for a few minutes on each side, just until they soften and begin to brown. Remove the slices to the baking dish. Season with a good pinch of salt and black pepper, sprinkle with some of the garlic-herb mixture, and douse with some vinegar. Repeat with the remaining slices, adding more oil to the pan as necessary, and layering and marinating the cooked zucchini similarly, until all of the zucchini is done and all of the herb mixture has been used up.

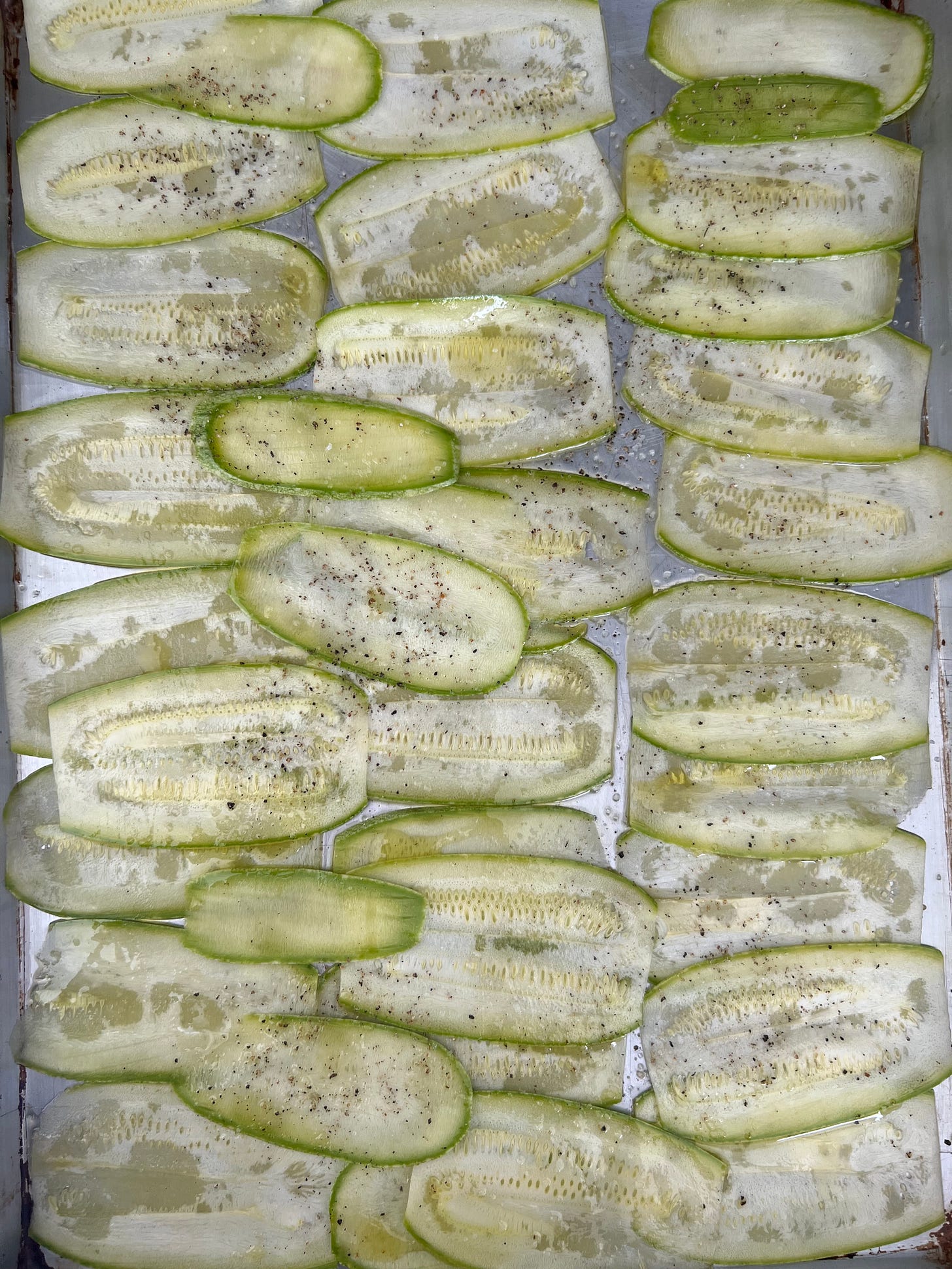

To make my version with thinner slices of zucchini, preheat the broiler. Using a hand-held mandolin, slice the zucchini lengthwise or crosswise just a couple of millimeters thick. Grease a couple of large sheet pans with olive oil and arrange the zucchini in a thin layer on the pans. The slices can overlap somewhat. Brush them with more olive oil and season them with salt and pepper. Place under the broiler, one pan at a time, for about 3 or 4 minutes, until they begin to bubble and brown. Remove from the oven and using tongs, gather up the cooked zucchini to transfer it to a baking dish. Sprinkle with some of the garlic-herb mixture and douse lightly with vinegar. Repeat with the remaining zucchini until all of it is broiled, layered, and marinated.

Let the zucchini sit at room temperature for at least an hour and up to a day to marinate before serving. Cover and refrigerate what’s left for a week or more. The thinner zucchini can be packed in a jar for storage and will keep up to a month if you always use a clean utensil to scoop it out.

A Note About Cooking in Olive Oil

You will no doubt see and hear people, even famous chefs, adamant that you should never use extra-virgin olive oil for frying, that its “smoke point” is too low and you’ll ruin whatever you cook. Having lived and cooked in Tuscany, Lombardy and Torino throughout my career, I can say I only ever saw Italians at home or in restaurant kitchens fry in EVOO, and to wonderful effect. It’s hogwash that you can’t sauté in it. Granted, restaurant burners, especially in French or Chinese kitchens, may be set at hotter temperatures than those in Italian ones. I once heard a sexist Italian chef (redundant?) critique the French for “raping” their food with too-high heat, rather than making love to it the way the Italians do, so there’s that. But at home you run very little risk of over-heating your olive oil.

That said, there is no need to use the finest extra-virgin olive oils for frying. They are expensive and tests have shown that most of the organoleptic differences between quality oils disappear when heated. I have an inexpensive, but still good-quality extra-virgin olive oil for cooking, and better oils for finishing and flavoring dishes. The newly rebranded Spanish oil producer Graza sells both at a reasonable price. But I like to try different ones from time to time.

This sounds like a book I need to have (ordering it today). Meanwhile, I looked at a recipe in my Flavors of Puglia, "Verdure a Scapece," which came from a restaurant in Acaia, a tiny walled town east of Lecce. The town is no longer tiny, the restaurant apparently no longer exists, but the recipe is still good and very similar to yours and Leah's, except with the addition of anchovies. Lots of authoritative sources credit these various sorts of semi-pickled vegetables (and fish) to the Mediterranean Jewish kitchen. I'm not sure why exactly but it seems to be a universal belief. Thanks for recalling it, Mitchell. In Puglia, as you probably know, eggplant (which Artusi calls a "Jewish" vegetable, is also treated this way.

Thanks, too, for your smart and sensible advice about cooking with evoo. I am so tired of correcting American chefs (and many, many home cooks) on this point. One of the most famous chefs in the country parroted this nonsense to me. Maybe they will listen to your guy-chef talk and step up to the stove (the piano).

I’m so glad you enjoyed the concia!