Issue #148: Sichuan Eggplant

My Favorite Vegetable, A Dish from My Youth, Nothing's Fishy about this Fish Fragrant Eggplant

As anyone who knows me will attest, I am a vegetable lover. Raw or cooked, roasted or fermented, the range of flavors, colors, textures, and tastes among vegetables never ceases to amaze me.

But if I had to pick a favorite, only one, it might be eggplant.

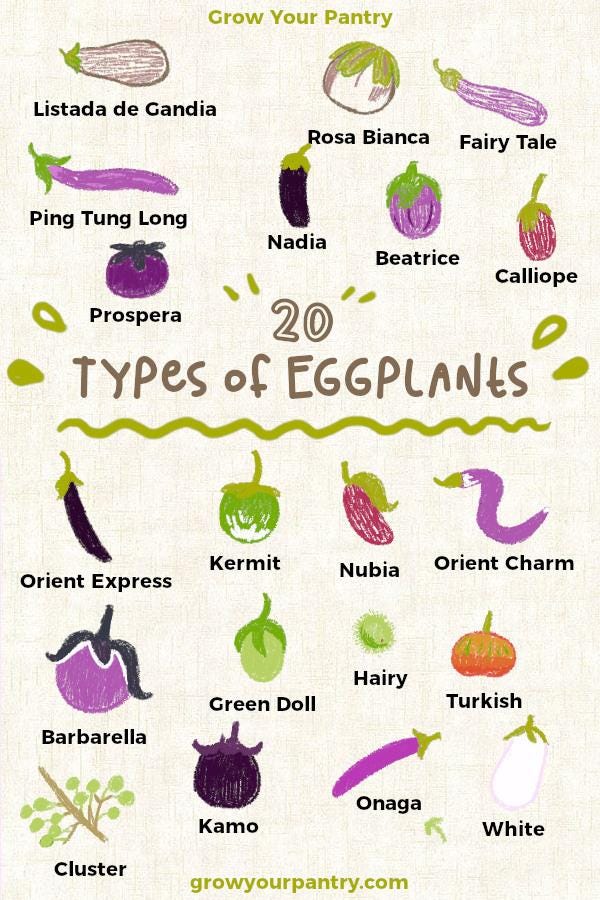

The Vegetable Varieties for Gardeners database assembled by the Cornell University Cooperative Extension lists 175 different varieties of eggplant. Most of us only ever see one. (It’s fun to scroll through their list.) Over the years I’ve been shopping at the Union Square Greenmarket in Manhattan, perhaps one of the biggest changes I’ve noticed has been the increase in the variety of eggplants grown by local farmers.

In addition to the variety within Solanum melongena, I love the variety of flavors and textures you can get from any one eggplant. Fry it to make it crisp. Roast it to make it soft. Salt it to make it ferment. Fry and then braise it to make it creamy. In my opinion, one of the only cardinal sins you can commit with eggplant is to undercook it, which leaves the flesh tough and bitter.

That said, one of the most interesting and memorable eggplants I’ve ever eaten was served to me raw as an appetizer in a yakitori restaurant in Tokyo. Known as mizu nasu or “water eggplant,” this Japanese variety is sweet and crisp enough to eat raw, like an apple. It tastes like fruit. We dipped wedges of raw eggplant into miso and they were delicious. Mizu nasu is a specialty of Osaka. My mind was blown.

I’ll venture that eggplant is a favorite vegetable of many of my social media followers, too, given the popularity of a recent Reel I posted of a sizzling pan of Fish Fragrant Eggplant. The recipe comes from Fuschia Dunlop, the doyenne of Sichuan cooking for the English speaking world. Like her, I love this dish.

A few things to say about Fish Fragrant Eggplant. First off, there is no fish in it. The name, Dunlop explains, is a translation from the Chinese yuxiang giezi that refers to the combination of flavors also typical of traditional Sichuan fish preparations. Since everyone who sees the name, assumes the eggplant is made fragrant with fish, including my husband Nate, who is not a fish lover, this can pose some awkward moments when you are asked, “What’s for dinner?”

During my youth in Toronto, Sichuan food was becoming quite popular. My sister and I often ate in Chinatown’s Sichuan restaurants. We always ordered what was in those days called “Sichuan eggplant.” Perhaps a little sweeter and a little less spicy than Dunlop’s version, I can still recall the savory tartness and silken texture of the dish. Word on the street was that ketchup was the secret ingredient. In memory of that dish, and to avoid those awkward moments with my husband, I’ve chosen to call this dish Sichuan Eggplant.

In fact, the flavor backbone of Fish Fragrant Eggplant, as for many Sichuan dishes, is the spicy, fermented bean paste known as doubanjiang. (Doubanjiang is also one source of the red color that is a hallmark of Sichuan cooking and that perhaps may also help explain why ketchup was thought to be a key ingredient and may even serve as one in a pinch.) Like Japanese miso or Korean doenjang—both of which owe their origins to the Chinese technique of fermenting beans—doubanjiang is made by salting, inoculating, and aging beans, in this case, broad beans or favas. Rich in umami, salt, and spice, it provides an injection of deep, complex flavor to all sorts of Sichuan dishes.

The most common and traditional doubanjiang comes from the region of Pixian, outside of the Sichuan capital of Chengdu. It is chunky and funky and complex. I’ve been working my way through a kilogram of this stuff for years. But a very fine and easy-to-find chili bean paste that’s not too spicy, but still has plenty of flavor is made by the ubiquitous Lee Kum Kee brand, who uniquely transliterate the name as toban djan. In my opinion, theirs is well suited to this dish.

Like many Chinese dishes, Fish Fragrant Eggplant requires a two-step cooking process, but that doesn’t make it difficult. First you cook the eggplant, and then you make the sauce, into which you add back the eggplant to braise. Traditionally, and surely in those Toronto Sichuan restaurants, the eggplant was deep fried. To avoid wasting precious oil and calories, I try to avoid deep frying at home. In this version I pan fry the eggplant, but it can also be roasted.

I made the Sichuan Eggplant I posted on Instagram for lunch the other day because I had a couple of Asian eggplants—the long, skinny, light purple kind—that were just about past their prime. Parts had become soft, so I cut them away. Because of their thin skin and delicate texture these eggplants are the preferred variety for this dish. They are increasingly common—moving the tally of eggplant varieties readily available in the marketplace up to two!—but you can use any type of eggplant for this dish, save for the small, round bitter green Thai eggplants you can sometimes find in Asian markets. The key is to cut the eggplants into small pieces of equal size so it cooks evenly and can be eaten easily. Dunlop recommends long, thin wedges or batonnets, but I like to use the popular Chinese roll cut for Asian eggplant. Both are fine.

Given the relatively few ingredients, and assured success, this is a good gateway dish for those intimidated by Chinese cooking or for those who’ve tried it and been disappointed by the results. It helps to use top-quality condiments, such as those sold by the Mala Market. But you’ll find everything you need in just about any good grocery store or certainly any Asian market.

Recipe: Sichuan Eggplant (aka Fish Fragrant Eggplant)

(Makes 4 servings as a side dish or light lunch)

2 to 3 medium Asian eggplants, roll cut into 1-inch chunks or sliced into 2-inch-long wedges

4 tablespoons peanut, grapeseed, or other neutral oil

1 1/2 tablespoons spicy chili bean paste (aka doubanjiang or toban djan)

1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh ginger

1 tablespoon minced garlic

2/3 cups water or stock

1 1/2 teaspoons sugar

1 teaspoon light soy sauce

2 teaspoons black Chinkiang vinegar

4 scallions, chopped

Salt and freshly ground white pepper

1 teaspoon cornstarch mixed with 1 tablespoon water to make a slurry

1 teaspoon toasted sesame oil

Heat a work or large skillet over high heat. Add about 3 tablespoons of the oil and once smoking hot, add the eggplant, tossing immediately so that the oil is soaked up by just one or two pieces. Stir fry until the eggplants are browned on all sides and almost cooked through, about 5 minutes. I find simply tossing doesn’t always do the trick of evenly browning the eggplant, so I use tongs to turn individual pieces to make sure every surface comes into contact with the hot wok. Once cooked, remove to a bowl and set aside. Alternately, you can toss the eggplant with the oil and roast in a 400°F. oven for 15 to 20 minutes, until soft and browned around the edges.

Add the remaining tablespoon of oil to the wok. When hot, add the chili bean paste and cook for about 30 seconds, until it gives off a strong flavor and turns the oil red. Add the ginger and garlic and cook for 30 seconds more. Add the water or stock, sugar, and soy sauce. When that begins to simmer, add back the eggplant. Cook for a few minutes until the eggplant absorbs some of the sauce and is totally cooked through. Add the black vinegar, chopped scallions, a pinch of salt, and a grind or two of white pepper.

Stir in the cornstarch slurry and continue simmering just until the sauce thickens. (That’s the point at which I took the video for the Reel, above.) Remove from the heat, drizzle with sesame oil, and serve with plenty of steamed rice.