I am writing this week from Tokyo. A wacky, wonderful city I love. Tokyo is my answer when anyone asks what’s my favorite food town. That may be a pretentious, cliché response. But the Japanese devotion to craft and obsession to detail, coupled with a complex mixture of curiosity, custom, and pride, fill every visit with gastronomic surprises and delights.

I’ve been fortunate to have close friends with an even bigger obsession with Tokyo and Japan than mine. In fact, theirs lit my own. Soon after my high school friends Judi and Marcus moved to Tokyo for work in 2000, I came to visit them without much interest in Japan or Japanese food, to be honest. I just hadn’t been exposed to much at the time. Having spent my junior year abroad in Paris and having studied and cooked for a year after college in Italy, I was sure I’d already found my culinary happy places. But seeing old friends and having a place to stay in Japan afforded me an opportunity to explore.

Ten days in Tokyo changed everything.

While I still love the food of France and Italy and so many other places around the world, I believe the seriousness with which the Japanese approach cooking and eating sets them apart from just about everyone else.

I made a couple of return trips to Japan during subsequent months and years. Continual discoveries made by Judi and Marcus and the help of a growing network of friends led me to write a lengthy, multipart article called Twelve Restaurants in Tokyo for The Art of Eating that was nominated for a James Beard Foundation Journalism Award in 2003.

After meeting Nate, our first trip to Japan together made me a little anxious, I’ll have to admit. Was he going to like it here, too? Would this be one of “our places?” It didn’t take long for me to find out. Waiting on the platform for the Narita Express train to get from the airport to the city, we watched an army of uniformed workers line up as the train rolled in. They bowed in unison before setting about to clean the train before we were allowed to board. He turned to me and said, “I love it here.”

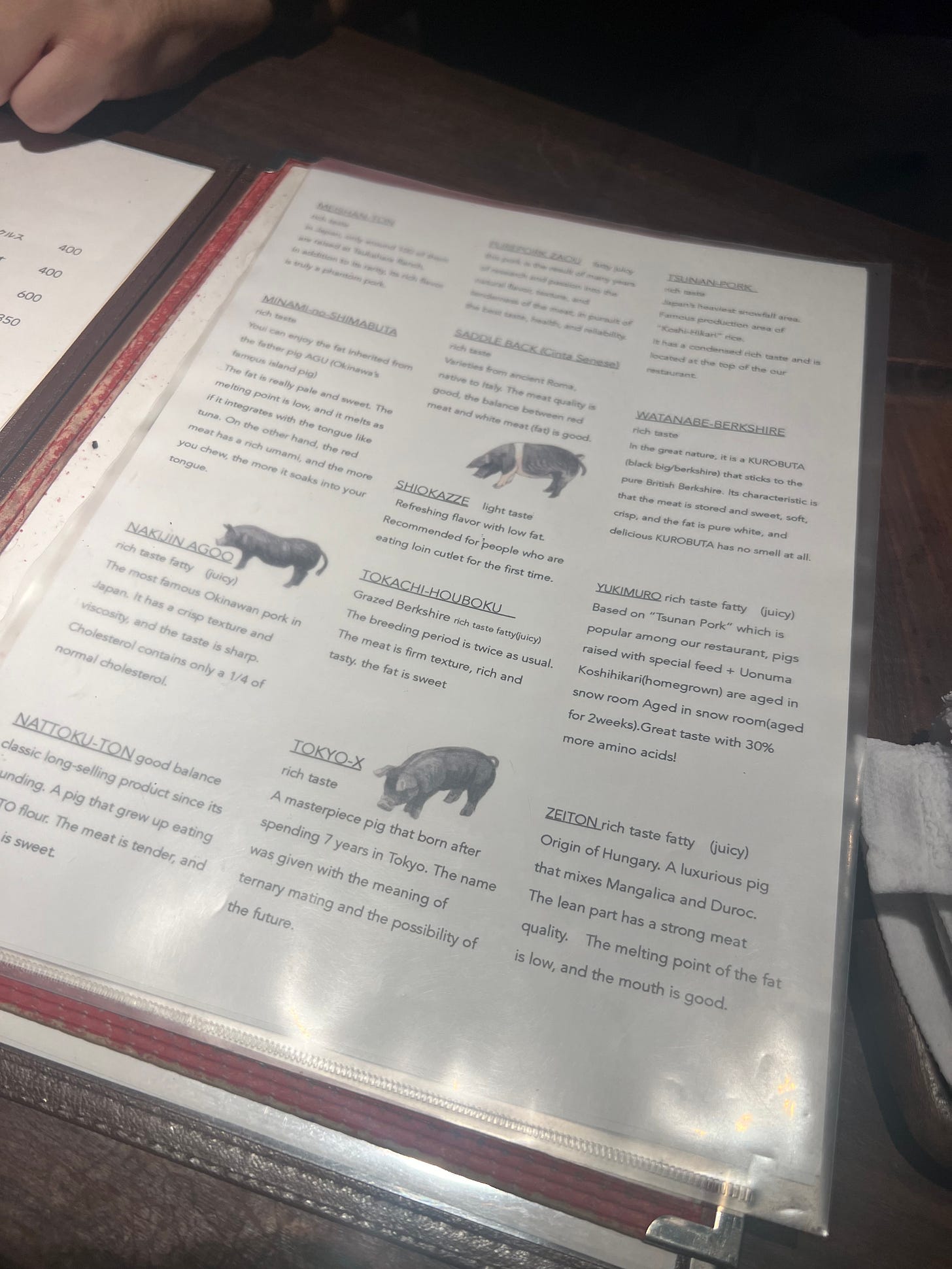

Although there are many other things that Nate loves about Japan, high on his list is tonkatsu, the crispy-fried, breaded pork cutlet that takes center stage in restaurants devoted to its perfection, in the katsu sandos made on fluffy shokupan you find in train stations and convenience stories all over town, on steaming bowls of rice known at katsudon, and in fast-food curry house chains that specialize in katsukare. What’s not to like?

The quality and flavor of the pork, the evenness of the crisp panko coating—panko is the fluffy white Japanese bread crumb that gives Japanese fried foods their particular crunch—and the precision of the cooking are keys to the best tonkatsu. But, like pizza, fried rice, and pad Thai, even just a mediocre tonkatsu is still pretty good.

Back when we rented a house up in Ithaca New York, I had easy access to beautiful, locally raised, thick-cut pork chops at the Greenstar Food Co-op. With those chops I start making tonkatsu pretty regularly at home. Although I left the bones in my chops, which would be unheard of in Japan, the results tasted remarkably authentic.

Once you’ve found a good chop, cut about an inch thick is ideal, tonkatsu simply relies on the common classic breading technique to produce its golden crust: a dusting in flour, a dip in beaten egg, and a roll in fluffy panko bread crumbs. (Once relatively obscure, panko is now available in just about every grocery store, even in rural New Hampshire.) I fry my tonkatsu in peanut oil, but any neutral vegetable oil will do. (At Butagumi, where we ate last night, they use pure sesame oil for frying.)

For the home cook, I think the most difficult part is getting the doneness right. It takes longer to cook the thick chop than you think. But cook it too long and you’ll be disappointed with the result. If the pan is too hot, the breading will burn before the meat is done. If it isn’t hot enough, the tonkatsu won’t crisp. I use a good cast-iron pan for even heat distribution and rely on a good instant-read thermometer to get to the right juicy, medium-just-this-side-rare point (about 135°F). The thicker the chop the more challenging it is to get it all just right.

My Instagram feed is filled with Reels of people looking for the biggest, thickest tonkatsu in Tokyo. They are ridiculous and impressive. Don’t get carried away.

I’ve made tonkatsu so often at home I’ve had the opportunity to experiment and evolve my technique. I now marinate my pork in shio koji, a salty, fermented brine that I first learned about in a cookbook by the Michelin three-star chef Kyle Connaughton of Single Thread, who was the head chef of a celebrated restaurant in Japan for many years. I slather my chops with shio koji and let them marinate for a day or two before I freeze them so that upon defrosting I’m ready to fry. You can read more about this marinade and technique here, but it isn’t necessary to make a perfectly delicious tonkatsu when you are just starting out. A simple salting will suffice.

At Butagami in Roppongi last night, the tonkatsu was about as classic as you can find. We were able to choose between either the fattier rossu (sirloin) or leaner hire (loin) cut from whatever variety of pig they had available. Once breaded, fried, and sliced, their near perfect tonkatsu was served traditionally with shredded cabbage, rice, and miso soup, each as caringly selected and prepared as the pork. For condiments, tonkatsu sauce (a Worcestershire-rich you can also make at home), mustard, and salt. It’s hard to think of anything more simple or more satisfying.

RECIPE: Tonkatsu, Japanese Fried Pork Chops

Makes about 4 servings

2 large, thick-cut pork loin chops with a decent amount of marbling and fat (about 1 1/2 pounds)

Salt

1 cup all-purpose flour

1 egg

2 cups Japanese panko breadcrumbs

1 to 1 1/2 cups peanut or other vegetable oil, for frying

Shredded green cabbage, miso soup, steamed rice, and Bull-dog sauce, for serving

About an hour or two before cooking, remove the pork chops from the fridge. Generously season with salt on both sides and let sit on a plate at room temperature until ready to cook.

Place the flour on a plate. In a wide, shallow bowl, beat the egg with 2 tablespoons of water and a pinch of salt until well blended. On a second plate, spread out about half the panko. Arrange these three plates side by side—flour, egg, panko—and place another large, clean plate on one end. Line a baking tray with a metal rack.

Into a large, cast-iron pan, pour about ¼ inch of oil and set over medium-high heat. While the oil heats, pat the pork chops dry with paper towel. Dredge the first chop in the flour to evenly coat, being sure to get the edges of fat and bone covered, too. Dip the floured chop into the egg, again making sure every surface is coated. Allow any excess egg to drain off before you lay the chop on the panko. Pat and press the panko onto ever surface of the chop until it has a nice, even coating, and lay the breaded chop on the clean plate. Repeat with the second chop, using more panko as necessary.

By now the oil should be good and hot. Lay the chops into the hot oil and let cook for a couple of minutes to set the coating. Reduce the heat a notch or two and continue cooking another 7 or 8 minutes, until the panko coating is golden brown. Pay close attention, raising or lowering the heat until there is a steady fry that cooks without burning. Once the first side is nicely browned, carefully turn the chop over with tongs to cook and brown the second side. Turn up the heat for a minute or two, then lower it again for more even cooking. You may have to add a little more oil to the pan to keep the sizzle going, but just do so a little at a time so the oil can come back up to temperature without interfering with the frying.

When the second side is getting nicely browned, about 5 minutes, stick an instant-read thermometer in the center of the chop near the bone to test for doneness. You are looking for about 135°F. Keep frying until you get there. If the edges are not browned, raise the temperature a little and carefully hold the chop upright with tongs, adjusting the chop so that the edges press against the bottom of the pan. Once done, carefully transfer the pork chops to the rack and let sit for 3 or 4 minutes to settle. The internal temperature will continue to rise while it sits.

To serve, slice the loin meat off the bone and then slice loin into strips (as shown). Arrange on a serving plate or individual plates and serve with shredded green cabbage, miso soup, steamed rice and Bull-dog sauce for an authentic and truly satisfying Japanese meal.

Hi, Nancy! Admittedly, I’m no expert. But for meat I just use my Shio Koji as a sort of dry brine (even though it’s wet!). I coat the meat and let it sit as long as I can, an hour or a day or two, depending on how thick or thin the piece and what time I have. The freezing is for storage, not the marination. It’s like adding salt plus, a kind of fermented umami flavor that has ads a delicious backbone of flavor. It may even tenderize a little, though I’m not sure.

Mitchell, could you explain a little more about using Shio koji as a marinade, please. You said you coat the chops and then freeze them until you're ready to cook. But is freezing an essential part of the prep or is it just a convenience? And if the latter, how long would you marinate a thick pork chop in Shio koji? I ask because I have a jar of the stuff in my fridge, left there by our mutual friend Naomi, and I have yet to figure out how to use it. Thanks for any advice! The post makes it all sound incredibly delicious!