Issue #68: Mustard Shortage Solved

Climate Change, Making Dijon-eque Mustards, Both Grainy and Smooth

I’m back in Tel Aviv, where it has been 90°F. and sunny every day. It's hard to imagine how we will cool the planet when the vicious cycle of warmer weather and increased consumption of energy, water, and everything else will break. There’s an answer to be found somewhere in how we grow, distribute, cook, and dispose of our food, but we’ve got a long way to go. In the meantime, I offer you a way to make your own mustard. Thank you for your continued support and enthusiasm for Kitchen Sense. Please share it!—Mitchell

So, there is a mustard shortage in France. Photos of empty shelves, from where bottles of moutarde de Dijon once beckoned French shoppers, are all over the Internet. Exposés of salades undressed, steaks sans condiment, naked rognons de veau are flooding the news.

The situation reminds me of the French butter shortage back in 2017, when the same press had a heyday reporting on panicked Parisians hoarding bricks of beurre demi-sel, attributed in part at the time to an increase in demand for buttery French Pastries from overseas countries, namely China.

While the panic about mustard may be real, the anglophone press’s sensationalization of the shortage mostly focuses on the crise gastronomique rather than the truly frightening reality that the mustard shortage is due in large part to climate change and war. Drought in Canada, the source of most of France’s mustard seed, has destroyed this year’s crop, and Russia’s war on Ukraine has interrupted other sources of mustard, thereby increasing European demand for the French product.

These sorts of shortages will only happen with more frequency and more severity as climate change and conflict wreak havoc on our food system. If you thought COVID shone a light on the fragility of our supply chains, wait until it’s not the chain but the supply that is interrupted irrevocably.

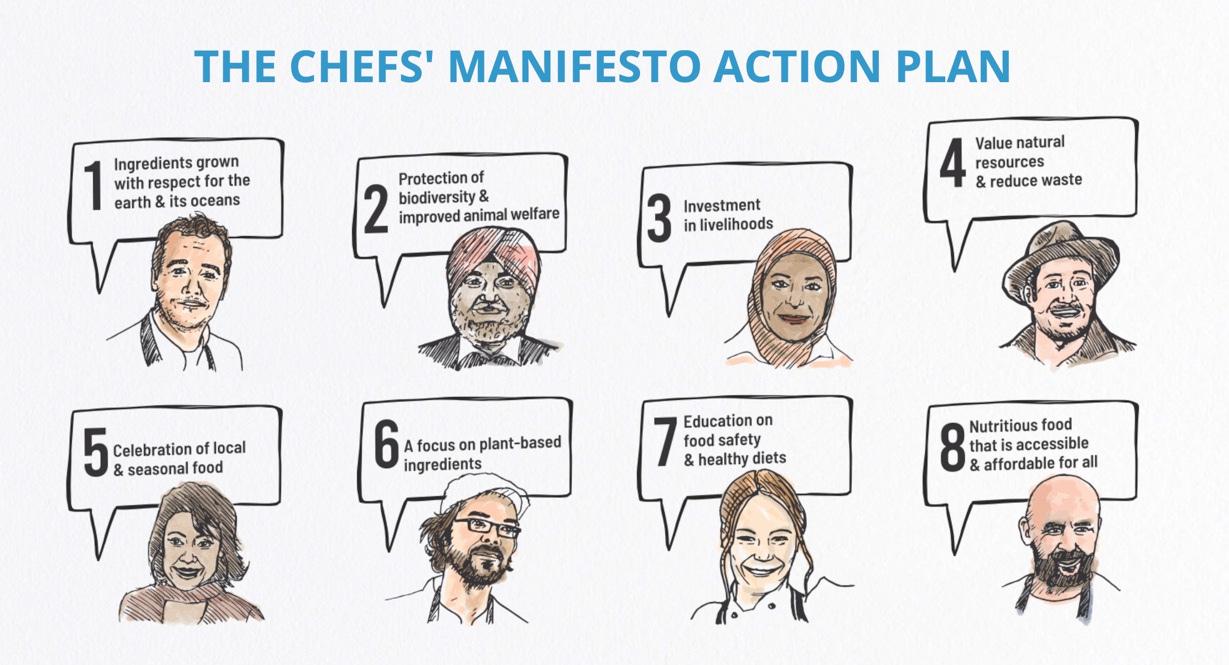

Coincidentally, I’m working with the Sustainable Development Goal 2 Advocacy Hub and their Chefs’ Manifesto project to plan a side event during the upcoming United Nations General Assembly in New York, for which we are gathering chefs to learn more about the urgent global food crisis and what they can do to help the immediate need while also supporting systemic change. It’s part of a new #HungryforAction campaign. The time to act was yesterday, but we must do all we can now to make better choices about how we eat.

I’ve been looking for ways to make my own Dijon-style mustard since long before this shortage was afoot. In fact, I confess, it wasn’t until I posted a photo of a recent batch of Dijon faite maison that a few of my followers informed me about the shortage, which had somehow escaped my constant doom scrolling on Twitter.

I’ve been making my own grainy mustard for decades, ever since I settled on a recipe for deli mustard to include in The Mensch Chef back in the early 2000s. But I never made a Dijon I liked enough to replace the real thing.

I am an avid consumer of Dijon mustard, which is always in my refrigerator. I use it as a flavorful, salty, umami-rich base for vinaigrettes, mayonnaise, sauces for fish, and as a seasoning for meat. Several years ago, when I first learned that Unilever had purchased Maille—once one of my favorite brands, whose beautiful Place de la Madeleine shop in Paris I frequented for their mustard on tap—for some reason I started reading mustard labels. To maille surprise (get it?), I found preservatives like sodium metabisulfite and potassium metabisulfite in almost every French brand, Maille included. You have to laugh when these preservatives are included on bottles labeled à l’ancienne, which is common.

Ever since, I’ve read every mustard label to avoid these preservatives, which seem totally unnecessary to me in a product that is by its very nature shelf stable. When I find a French Dijon that’s preservative free, such as the Moutarde Clovis from Reims pictured above in my fridge, I buy a few jars to stock up. Anything from France labeled biologique or bio for “organic” is likely to be free of these chemicals.

Still, I’ve always wanted to find a way to make my own.

Most Dijon I’ve made comes out too bitter, too pungent, and without the creamy texture that I like in the best Dijon. From what I’ve read, the commercial mustard is usually made with brown mustard seeds, which are less pungent than yellow. But ground yellow mustard is all I can find in the marketplace. This poses the first challenge to making a good Dijon chez moi. What’s more, I think there is vast variability in the quality and flavor of the ground mustard I can buy. Since my previous attempts at Dijon making, I’ve acquired a Vitamix, so I was hopeful its power could help solve the texture problem, perhaps starting from whole seed, as I do for my grainy mustard. But I wasn’t able to get it smooth enough, even with the that workhorse of a blender.

My research also revealed, surprisingly, that Dijon mustard is not a geographically protected designation. Despite being named for the main city in Burgundy, Dijon, whence this style of mustard originates, la moutarde de Dijon is not bound to any particular region or preparation. Unlike Champagne, Parmigiano-Reggiano, or Jamon Iberico, Dijon can be and is made anywhere.

Recently, an old recipe from 1999 by Molly O’Neill in the New York Times Cooking app caught my attention. There was something about her technique—reducing fresh grape juice, white wine, vinegar, and shallot, before adding it to ground mustard—that smacked of authenticity, even though when I re-read the ingredients listed on my favorite brands, all I saw were mustard, vinegar, and salt. O’Neill also added olive oil and honey, which really seemed out of place.

Though I followed it to the letter, juicing fresh grapes and all, in the end O’Neill’s recipe didn’t work for me. I’m not sure why. My result was a bitter, runny mustard that would be hard pressed to pass for Dijon, let alone to emulsify a vinaigrette. I had to double the content of ground mustard to get anything near the right consistency, which created a far too pungent potion, even after letting it mellow at room temperature for a day. I tasted it against the mustard in my fridge. The acid content was too low, the sweetness too high. I used some white balsamic vinegar, mostly because I wanted to get rid of it, which added both sweetness and pep, but that thinned the mustard even more. Xanthan gum helped thicken it up, but felt like cheating.

Further tinkering with the recipe produced a result I was happier with. I drew on a Thai approach to flavor balancing, by which I mean that rather than trying to mask the pungency and bitterness with sweet, I dialed up the acid and salt components to complement it. And then I had what I think was a brainstorm. One of my favorite ingredients—if completely out of place in a French mustard—is saikyo miso, a delicate, white miso from Kyoto, whose texture, subtle sweetness, and umami I find a welcome addition to most things. What if I could use miso to improve both the texture and flavor of the mustard without having to add so much more pungent mustard powder or sugar? Inauthentic, but effective. It worked pretty well.

While the recipe below is definitely not how most Dijon is made, the fact that the name is unprotected means I can call it Dijon anyway. Buyer beware.

RECIPE: Dijon-esque Mustard

(Makes about 1 1/4 cups)

1 cup fresh grape juice or apple cider

1 cup dry white wine

½ cup white wine vinegar, divided

1 shallot, minced

¼ teaspoon freshly ground white pepper

¾ cup (about 3 ounces) yellow mustard powder

1 1/4 teaspoons fine sea salt

¼ cup saikyo or other white miso

2 teaspoons honey (optional)

¼ teaspoon xanthan gum (optional)

In a small saucepan, combine the juice, wine, 3 tablespoons of the vinegar, shallot, and white pepper, and bring to a boil. Reduce for about 15 minutes until only about a ½ cup of liquid remains.

Strain this reduced liquid into a blender. (I like to add a teaspoonful or so of the cooked shallot that’s been strained out, too.) Add the mustard powder, salt, and about ¼ cup of white wine vinegar, Whir the blender to make a smooth paste, scraping down the sides from time to time, making sure no unmixed mustard powder remains on the bottom. If the texture is still too thin, you can add the xanthum gum, and whir it all again to combine.

Transfer the mustard to a small bowl, scraping everything out of the blender, and mix a few times to aerate. Let it sit uncovered for about an hour, stirring from time to time. As the mustard sits, it will thicken and the bitterness will dissipate. Stir again, taste, and adjust the seasoning as you see fit. Depending on the source and freshness of your mustard powder, the mustard can be unpleasantly bitter at first. You can mitigate the bitterness with additional vinegar and salt to bring the flavor components into balance. Use sweetness sparingly and note that the flavor of the mustard will continue to soften and the texture thicken as it sits. I like to leave my mustard out on the counter for 24 hours or so, stirring occasionally. Transfer to a jar and refrigerate until needed. It will keep indefinitely.

Simpler than the Dijon recipe above. I’m still convinced that if I could find a way to blend this to a fine purée, it would be closer to the original. But I haven’t been able to achieve the right texture yet. Note, you may be tempted to make this in your food processor, but it won't work. A blender is required to break down the seeds.

RECIPE: Grainy Mustard

(Makes about 2 cups)

1/3 cup (2 ounces) brown mustard seeds

1/3 cup (2 ounces) yellow mustard seeds

¾ cup white wine vinegar or apple cider vinegar

¾ cup water

1 small shallot or small piece of onion, minced (about 2 tablespoons)

1 teaspoon kosher salt

1 or 2 teaspoons ground yellow mustard (optional)

In a pint jar, combine the mustard seeds, vinegar, water, shallot, and salt. Cover and let sit at room temperature for 24 hours, until the seeds have visibly swollen. Transfer the ingredients to a blender and grind on high speed until you reach the texture of the mustard you desire. The mustard will froth on top at first and then the froth will subside. Noting that the mustard will thicken slightly as it sits, adjust the texture with ground mustard, if using. Transfer the mustard to a small bowl and let sit at room temperature for at least 6 hours and up to 24 hours to mellow. Store in an airtight a jar in the fridge indefinitely.