Issue #93: Sober Cook, Drunken Noodles

Chinatown Inspiration, Frying Tofu, Recipe for Pad Kee Mao, Prepping Ginger and Garlic for the Fridge

A couple of things before I begin this week’s recipe. I misnumbered last week’s issue, which should have been #92 and was instead sent as #91. That makes this week’s #93. We are approaching 100 issues, which is hard to believe, honestly. Coincident with the approach of that milestone, I was just notified that I am now a “Substack Bestseller with hundreds of paid subscribers,” which ain’t quite the New York Times list, but I’ll take it! Thank you for your continued support. To celebrate the upcoming 100th issue, I’m cooking up a fun promotion. Stay tuned.

In the meantime, a reader wrote to ask for advice on how to make the puréed ginger and minced garlic stores I referenced in the dal recipe of the real Issue #91. (Paid subscribers are able to request recipes, just fyi.) All I did was what Anita Jaisinghani told me to do in her book Masala. You’ll find the directions at the end of this post.

Also, there’s a new episode of What’s Burning for your podcast listening pleasure. This week I interview Bryan and Dahlia Graham of Fruition Chocolate Works, located in New York’s Catskills region. If you love chocolate, if you’ve ever thought about opening a small food business, if you live and/or work in a remote location, or if you just like listening to folks share their stories, you’ll want to tune in. You can find What’s Burning wherever you listen to podcasts or by clicking on this link. (You will also want to order Fruition’s very special single-origin bars and dark milk chocolate, which you can do here.)

I’m a noodle nut. Truly. I love noodles in just about every form, in every cuisine. And although I’m partial to pasta and other noodles traditionally made with wheat, I love a good rice noodle, buckwheat soba, or bean thread with all my heart.

Last week, on a particularly sunny day, I was walking around Chinatown in lower Manhattan, one of my favorite pastimes. On Grand Street I came across a woman selling fresh rice noodles and fried tofu from a cardboard box top. I recalled I had purchased some holy basil at the Union Square Greenmarket earlier in the week—I had been surprised to see it at this time of year. And so, with visions of Pad Kee Mao in my mind, I got in line for the noodles. When I got to front of the line, she only had one bag left, a little over a pound. Clearly meant to be. I took it home excited for dinner. (I didn’t buy any fried tofu because I knew I had some tofu in the fridge I would fry later.)

On Drunken Noodles and Basils

Pad Kee Mao, better known here as “Drunken Noodles,” is the kind of dish from another culture that’s a universal comfort food. (While similar, Pad Kee Mao is generally considered distinct from Pad See Ew because of the addition of spice and a larger variety and quantity of vegetables.) I use a “recipe” for Pad Kee Mao more as a guideline or template than a strict prescription. While the sauce is pretty much consistent from one batch to the next, I change up the other ingredients based on what vegetables and proteins I have on hand. The only thing that is absolutely required, imho, is one of the Asian basils, whether holy, Thai, or opal. The three are distinct, but to my palate, interchangeable in this dish and other Thai cooking. I have even used Mediterranean basil in a pinch, but it’s not the same.

Thai basil seems to come into New York City in waves. I can only surmise that a shipment arrives from somewhere (probably California) and is distributed widely, and if another doesn’t get here in time, there’s none to be had. There have been periods when I have traveled all over town to my regular sources, Chinatown markets, H-Mart, even a Thai grocer in Woodside, Queens, but was unable to find Thai basil for weeks. #supplychain. Ren’s Asian Grocery in Ithaca, New York, often has it in an industrial sized pack, but even they were out.

As a result, as a reflex, whenever I do see Thai basil, I buy it, whether or not I have any immediate intention of using it. This forces me to think of Thai things to cook, which I enjoy. I also plant Thai basil on our terrace so I know I will have access to it toward the middle of the summer. This is my second year growing it from seed. I had so much Thai basil at the end of the season last year that I invented a Thai basil pesto using toasted peanuts, garlic, and fish sauce, and made a giant batch of it for the freezer. It’s delicious on fish and pasta.

Rice Noodles: Fresh, Firm, and Dried

Anyway, about rice noodles. Although I dabble, I’m no expert on Thai cooking. I recognize Thai food as one of the great cuisines of the world and feel like I could eat my way around Thailand for the rest of my days and never plumb all of its depth and variety.

Like most noodles, fresh rice noodles are Chinese in origin. Wheat noodles are from China, too, though prideful Italian culinary historians insist they were invented simultaneously in Italy. (What everyone seems to agree on is that the Marco Polo story of bringing noodles back from China and introducing them to Italians is myth.) I like the irony inherent in the world’s fascination with ramen as the most Japanese of Japanese foods, while the Japanese consider ramen Chinese food. Lucky for us, rice noodles in many forms have been adapted into many Asian cuisines.

When freshly made, as the noodles I bought on the street in Chinatown were, they have an incredible texture. The Japanese use the word for earlobe, mimitabu, to describe the sort of bouncy, soft but chewy texture of a fresh rice noodle. Once refrigerated, that texture disappears and the noodles harden to the point they can crack. Fresh noodles that have been refrigerated will soften again during cooking. One trick is to microwave them in the open bag for a minute or so to soften them before slicing and cooking, which speeds things up. Though nothing really compares to the texture of them freshly made and held at room temperature until they are cooked that first day.

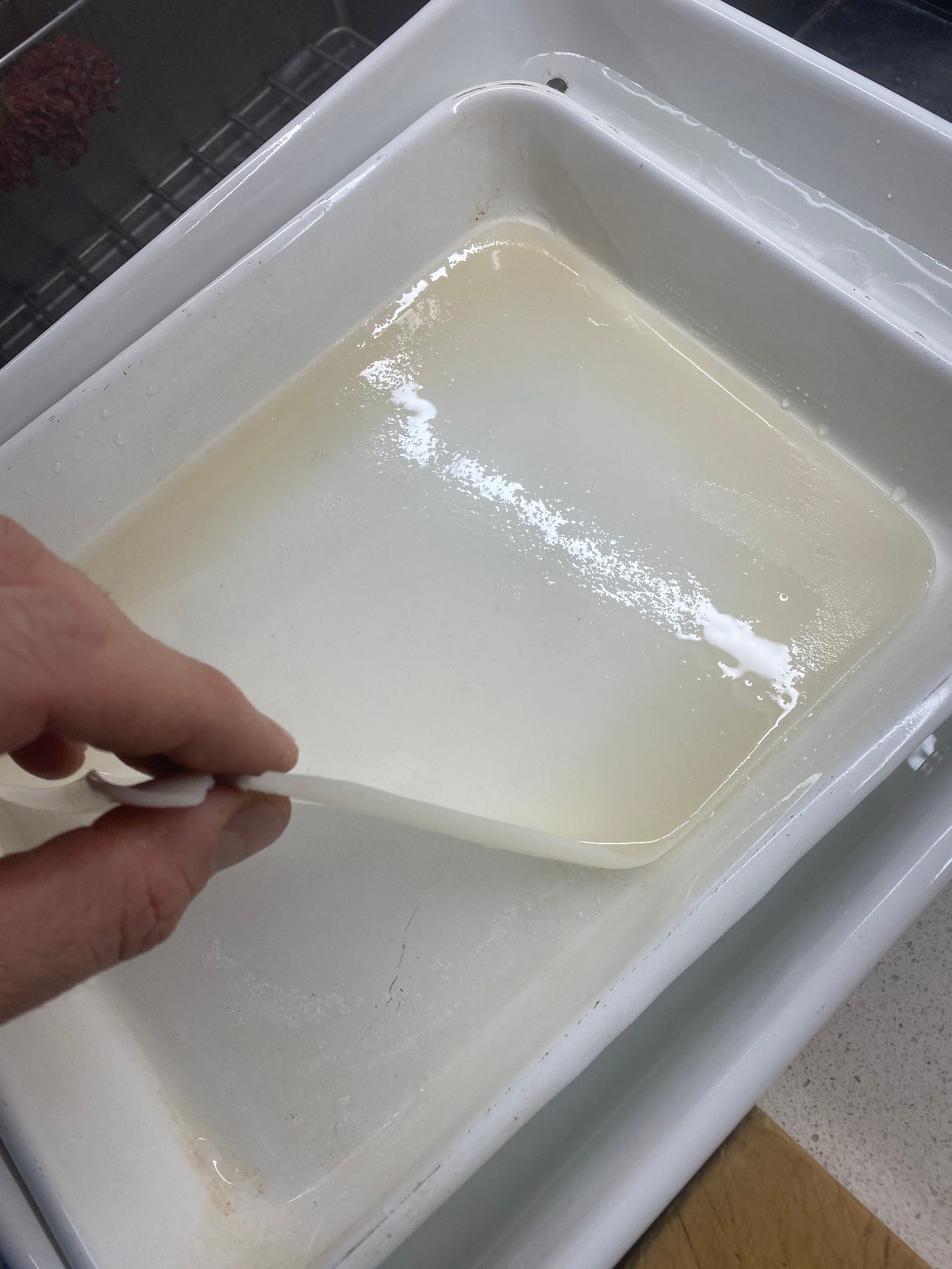

I have actually made fresh rice noodles several times myself following a technique explained by Woon Heng here. It was simple enough and quite satisfying. The hardest part was finding a tray that would fit in my steamer. But otherwise, the noodles were easy. Because the only tray that fit was quite small (I guess it is really my steamer’s fault), it took a long time to make enough noodles for a meal. So I haven’t done it often.

Dried rice noodles are also pleasant—think Pad Thai—and can be substituted for this dish, though the final effect will be quite different, without any of that mimitabu quality. Dried noodles need to be reconstituted in hot water until soft. Sometimes, when soaking isn’t enough, they need to be boiled. I recently purchased some slightly thicker than usual dried Vietnamese rice vermicelli that must have been made with diamond dust. They were so hard that I had to boil them for 10 minutes to soften them enough to eat.

Anyway, if I were you, if you aren’t going to make the rice noodles yourself, I would file this recipe away until you come across that miracle of confluence, fresh rice noodles and Thai basil both in the marketplace at the same time. Stroll often through a Chinatown near you and your chances of that sort of harmonic convergence will increase.

A word on the name. Why drunken? Like most food names, no one is sure. Did the Chinese originally make the dish with rice wine? Was the inventor drunk when he threw these things together? Do they help revive a drunken reveler before heading home? I dunno. And I don’t really care. What’s in a name? Mine aren’t traditional, anyway. Just don’t be drunk in the kitchen.

RECIPE: Mitchell’s Pad Kee Mao or “Drunken Noodles”

(Serves 2 to 6, depending on your self control)

For the sauce

3 tablespoon Thai fish sauce

2 tablespoons oyster sauce

2 tablespoons light soy sauce

1 teaspoon dark soy sauce

1 teaspoon sugar

¼ cup or more chicken or vegetable stock, or water

For the noodles

16 to 20 ounces fresh rice noodles (8 ounces wide dried rice noodles can be used in a pinch)

7- to 8-ounce block firm tofu

4 tablespoons peanut or other neutral oil

½ cup chopped allium of some kind, such as flowering chives, garlic chives, yellow chives, shallots, scallions, leeks, ramps, or onions

4 large cloves garlic, minced

1 or 2 fresh Thai or other chili, seeded and minced, or pinch dried chili flakes

5 ounces or so raw protein, such as thinly sliced chicken breast, beef, or pork, or shelled shrimp, or 4 ounces thinly sliced cooked protein, such as bbq pork (char siu), roast duck, or other meat (optional)

Salt

8 ounces (2 cups) or more chopped vegetable, such as yum choy or gai lan (Chinese broccoli), leaves separated and stems chopped, bok choy, Chinese cabbage, thinly sliced carrot, or what have you, alone or in combination

1 cup, packed, leaves of Thai, holy or opal basil (from a large bunch)

To prepare the sauce, in a small bowl combine the fish sauce, oyster sauce, light soy, dark soy, and sugar. Stir to combine and set aside so the sugar dissolves while you prepare the remaining ingredients. The sauce can sit, covered, at room temperature for a day or more.

If your rice noodles are freshly made and still soft, slice them into 1-inch-wide strips. Don’t worry if they are rolled up, they will unravel when they are cooked. If they’ve been chilled and are hard, you can soften them in the microwave for a minute or so until softer and then slice them. If using dried noodles, place in a wide flat bowl or pan and cover with boiling water to soak until softened.

To fry the tofu, slice the block of tofu about ¼-inch thick and then cut the slices into 1-inch slabs, more or less rectangular. Lay the sliced tofu on a sheet of paper towel and pat dry. In a large, nonstick or well-seasoned cast-iron frying pan, heat about 2 tablespoons of the oil over medium-high. Lay the slices in a single layer in the pan and fry until golden brown, 4 or 5 minutes. Using a fork, flip the tofu and fry the second side, another 3 or 4 minutes or so. Remove the slices to paper towel to drain and set aside. The tofu can be fried in advance. (I like to keep some in the fridge for snacking.)

Heat a wok or large frying pan (if big enough, you can use the same one you used to fry the tofu in) and add another tablespoon or two of the oil. Add whichever alliums you are using and stir fry for a minute or so until softened. Add the garlic and the chili and cook another minute or so. If using raw protein, season with a pinch of salt, and add it now and stir fry until just about cooked through. Add the vegetable, and cook until softened, stirring constantly. If using Chinese broccoli, add the chopped stems first to soften before you add the leaves. Once the vegetables are just about cooked.

Add the fresh rice noodles. If using dried, drain the reconstituted noodles well and add. Toss with the ingredients in the wok to distribute. If your fresh noodles are still rolled up tight, don’t worry, as they heat and you toss they will loosen up. Using a soup spoon, mix the sauce again, and then spoon it into the wok, drizzling it around the noodles, stirring between additions. You should use all of the sauce you have. If using cooked protein, add it to the pan now.

Continue cooking, stirring constantly so the noodles don’t stick. Add a few tablespoons of stock to help loosen and soften the mixture. (If using dried noodles, you’ll need to add considerably more stock.) Add the fried tofu, stir, add a little more stock, if necessary, and add the basil leaves. Turn off the heat and continue tossing until wilted. Serve immediately.

Ready-to-Use Garlic and Ginger

Although the idea of keeping ginger purée and minced garlic in the fridge is not new or unique, especially in Indian households, it was cooking my way through Anita Jaisinghani’s book Masala that made me start prepping it. Now I have ginger and garlic ready for everything, not just Indian food, but Italian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, you name it. I use the ginger in baking, too. Here’s the technique:

To make the ginger, you can use any amount that will gain traction in your blender, but about 1 pound makes a good pint jar of purée. Look for fresh, plump juicy ginger. Trim the ends and any bruises or moldy parts, but there is no need to peel it. (During college I worked for an excellent Thai chef who never peeled garlic, either.) Cut it into chunks and place in a blender along with ¼ cup or so of water. Pulse to purée to a paste, making sure the fibers are broken down. Add more water if necessary to keep it moving until properly puréed. Transfer to a jar and store in the fridge for up to a month or so.

To make the garlic, you’ll need a cup or two of peeled cloves, from 5 or 6 heads, depending on size. For this, a food processor works better than a blender, as you want a mince, not a purée. (Puréed garlic is so broken down that it oxidizes quickly and develops a bitter flavor.) Transfer to a jar, press down with the back of a spoon or spatula to remove any air pockets, and cover with a ¼ inch or so of olive oil to prevent excess exposure to air. Cover the jar and refrigerate until needed, replenishing oil to cover as necessary. I keep it also about a month, which is probably too long, but I can’t throw anything out.

This has inspired me to order tonight's dinner from Long Grain, my local top-drawer Thai restaurant, which I think you know well, Mitchell. Very very yummy.