Soy Sauce Chicken to Go

Making a Chinese Banquet on the Road, Leftover Chicken Science, Steaming Greens

I hope those of you in the US and Canada had a good holiday weekend. For Issue 7 of Kitchen Sense, we turn to the Chinese kitchen, one of my favorite cuisines to cook and to eat. If you’ve considered making Chinese food, but have hesitated, Soy Sauce Chicken is a good place to start. It’s relatively simple, hard to mess up, doesn’t require any special equipment, and delivers on flavor. I believe most everyday home cooking around the world has simplicity in common. The challenge of veering away from one’s usual repertoire is shopping for ingredients. But once you have them on hand, the cooking should be easy. At least I hope to be able to show you why I believe that to be true with this newsletter. If you are enjoying Kitchen Sense, please share the link. Consider subscribing. Give a gift. Thank you and enjoy.

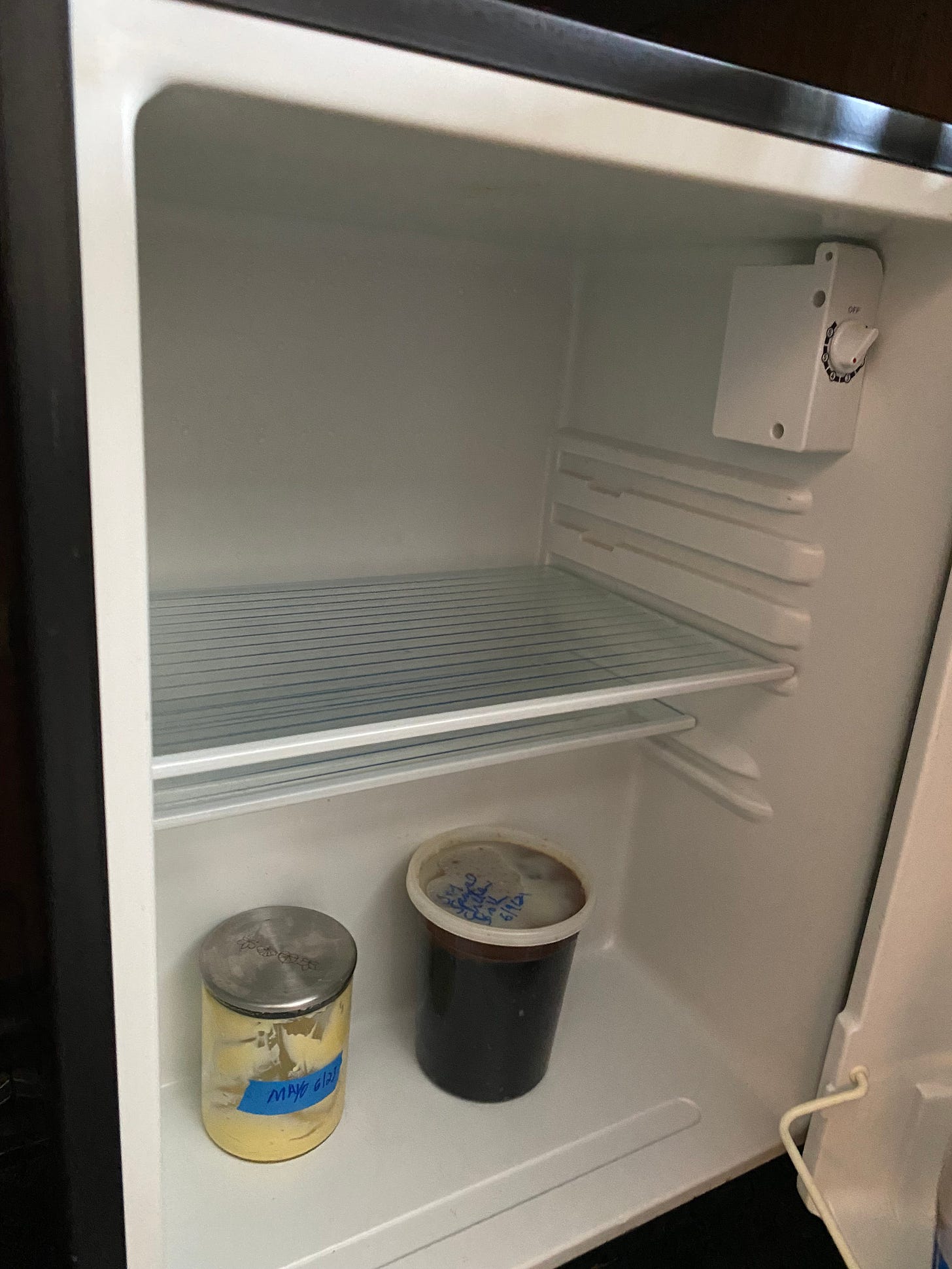

I am sitting in a hotel room in Portland, Maine, after a long July 4th weekend with friends in Rockport. We are here for a few days before the long drive back to our lakehouse rental in Ithaca, New York. The only thing in the fridge of our hotel room is a quart container of soy sauce chicken braising liquid. Oh, and some of my homemade mayonnaise (see Issue #6).

You might think it strange that I am traveling with a container of soy sauce chicken braising liquid. I know my husband, Nate, does. But after 15 years together he’s getting used to my culinary eccentricities. Which doesn’t mean he isn’t sometimes still embarrassed by them. We needed to find a hotel room in Portland that accepted dogs (#ohmilo) and that had a refrigerator in the room. Welcome to the Hyatt Place Old Harbor Hotel.

Here’s why I have the braise with me. The Rockport friends we stay with asked if I would prepare a Chinese dinner while we were visiting. (I do much of the cooking when we are all together.) The centerpiece of my Chinese meals these days is the classic, simple, and delicious Soy Sauce Chicken (See Yao Gai), which I always serve with the traditional condiment of ginger scallion sauce (more a sludge than a sauce, really). Soy Sauce Chicken (aka Red-Cooked Chicken) is a great course for a banquet because it can be made a few hours in advance, it doesn’t require a wok, and it is best served slightly warm or at room temperature. This frees up your hands, your pans, and your burners, which will otherwise be busy with last-minute stir-frying and other prep.

I’ve cooked a lot of Chinese food during the pandemic. I also cooked a lot of Chinese food before the pandemic. You may not know that I’m dedicated to the practice of Taoist Tai Chi and I’m on the national board of the Taoist Tai Chi Society of the USA, which is the US branch of the international Fung Loy Kok Institute of Taoism, based in Toronto. In addition to promoting the health benefits of Taoist Tai Chi and making it available to all, cultural exchange is a key part of the organization’s mission. Moreover, banqueting is a key part of the organization’s culture—an extension of tai chi, according to the organization’s late founder Master Moy Lin Shin—and so, with the help of many volunteers, I’ve cooked many a Chinese banquet for our local Tri-State Branch over the years, often for more than 100 guests.

The Secret to Good Comedy and Good Cooking: Timing

The most challenging thing about preparing a Chinese banquet, whether in a large banquet hall or at home, is the timing. In fact, I hear frequently that timing is the trickiest thing for people cooking in general. Due to the nature of Chinese cooking, timing can be even more complicated. Many dishes require a lot of advance prep—many hands make light work—and then a lot of last-minute cooking. It can be hard to juggle it all at the end. The key is to plan a menu accordingly, selecting dishes that use different techniques and that can be cooked at different times. Unlike other styles of eating, in a Chinese meal not all the dishes are expected to be ready at the same time, rather they are coursed and served in succession. To make it easier on the cook, some should be able to be served cold or at room temperature. If you do it right, the cook may even get a chance to sit and enjoy some of the food with the guests.

Soy sauce chicken comes in handy for these reasons. Plus, I think the version I make is particularly yummy. I’ve been using the same braising liquid for about a year now—maybe a dozen or more chickens have taken a dip. The richness of each chicken adds to the flavor of the next, as when you are making a double or triple French stock, but times ten. Occasionally, I add more aromatics to the braise so none of the individual flavors dilute. The result is rich, concentrated, and full of umami. It is also full of collagen. Chilled, it is solid like a rock. Mmm.

Why Didn’t the Chicken Drive to Maine?

When I was contemplating how I would make a Chinese banquet for ten people in someone else’s kitchen in a rural part of another state without a large Asian community, I worked through a few scenarios. I didn’t want to risk not being able to find ingredients. I decided to do as much as I could in NYC and bring the components with me. (Our banquet was scheduled for the day after we arrived, so the timing worked.) That amounted to preparing a bunch of marinades and dipping sauces to transport in tightly sealed jars. I steamed and chilled radish cake and measured flour for wrappers.

At first I thought I would cook the chicken at home, too, then pack it up to bring with us. But I recalled that many moons ago, when I TA-ed a meats class in hotel school, I read a food science article about what happens to chicken when it is cooked, chilled, and reheated. Both a physical and chemical change causes leftover chicken to have a different taste and texture. Don’t get me wrong, I love cold, leftover chicken. But as the centerpiece of a Chinese meal, I thought it needed to be made fresh. There is a certain silky, juiciness to a freshly cooked soy sauce chicken that is part of its charm. Soy Sauce Chicken can sit at room temperature for a couple of hours without altering the quality. But chilled and reheated won’t do.

I could have made the chicken from scratch on site. But despite several Facetime calls during which our hosts proudly pulled out bottles and packs of various Chinese ingredients from their pantry, I wasn’t sure I’d find everything I needed. And I also wouldn’t be able to recreate the concentrated flavor of my house braise.

At first I wasn’t sure I should keep the braising liquid. No recipe I could find advised one to do so. In the past, on the rare occasions that I made this chicken, I just discarded the liquid after the chicken was consumed. But these days I am more focused on not wasting food. And during the pandemic I recognized that I would likely be cooking Chinese food more regularly for a while. It seemed wasteful to just chuck it. I couldn’t imagine a frugal Chinese home cook pouring all that flavor down the drain. I stared at the pot of rich, dark, fragrant liquid for insight about what to do. I recalled seeing barbecue-meat-counter attendants in Chinatown capture all the liquid run off from the cooked meats they chopped, which I presume they reuse in something. I strained and saved the soy sauce chicken broth and have been using it ever since.

So, I packed my quart container of solid braising liquid (#oxymoron), along with the items I prepped and some other key ingredients—flowering chives, Chinese celery, long beans, yu choy—and we were off.

For the dinner in Maine, I made pork and chive dumplings (with homemade wrappers), dan dan noodles, tiger salad with smoked local tofu, Chinese celery, local peas, and cilantro, Sichuan smashed cucumbers, crispy stir-fried radish cakes with flowering chives, mapo tofu, steamed pork riblets with black bean sauce, and the soy sauce chicken with garlic scallion sauce. It was all a hit. A nine year old who doesn’t eat much of anything, couldn’t stop himself. Later he told his mom he’d never had such delicious food. The highest compliment a cook could imagine.

Of course, you don’t need to do all of this. A freshly made soy sauce chicken with a plate of greens and a bowl of steamed rice is a regal meal all by itself. You don’t even need to make a whole chicken. Do a few thighs, some breasts (with skin and on the bone, only, please), just reduce the cooking time accordingly. Try it. See notes at the end on some ingredients and substitutions.

RECIPE: Soy Sauce Chicken (See Yao Gai)

1 plump 4-pound chicken, backbone removed, cut in half lengthwise, or up to an equivalent weight of chicken parts (with skin and on the bone)

1 tablespoon kosher salt

4 tablespoons Chinese rose (mei gui lu jiu) or Shaoxing wine, divided

1 tablespoon peanut or vegetable oil

1 large shallot, thinly sliced

2 garlic cloves, peeled and smashed

1 2-inch piece ginger, peeled and thinly sliced

4 whole star anise

2 bay leaves

1 clove

1 2-inch cassia cinnamon stick

1 ½ cups light soy sauce

1 1/4 cups dark soy sauce

2 ounces (56 g) rock sugar or 1/4 cup dark brown sugar

¾ cup honey

¼ teaspoon ground white pepper

2 pieces dried tangerine rind, or 2 strips candied orange rind, or 2 strips fresh orange zest

5 scallions, white and green parts, cut into 2-inch pieces

Chicken stock or water, heated, as needed

Place the chicken halves on a large plate or in a rectangular baking dish. Rub the skin all over with salt and then massage in 2 tablespoons of the wine. Cover and refrigerate for at least 2 hours and up to overnight.

In a heavy, covered pot large enough to hold the chicken halves side by side, heat the oil over medium heat. Add the sliced shallot, garlic, ginger, star anise, bay leaves, clove, and cassia bark, and cook, stirring until fragrant, about 1 minute. Stir in the light and dark soy sauces, sugar, honey, tangerine peel, and scallions. Bring to a boil. Reduce the heat to a simmer, cover, and simmer for about 15 minutes. Add the remaining 2 tablespoons of wine. Lower the chicken halves into the simmering liquid, breast side up. You can manipulate them to fit tightly, so they are just barely covered by the liquid. If you need more liquid, add a little chicken stock or water. Bring the mixture to a boil, reduce the heat to a simmer, cover, and cook for 10 minutes. Skim any froth that collects on the top. After 10 minutes, turn the chicken halves over so they are breast side down, cover, and simmer another 10 minutes. (At this point the meat should have reached at least 155°F. on an instant-read thermometer. It will rise further at first as it sits.) Turn off heat, keep covered, and let sit at least 10 minutes and up to 2 hours.

Before serving, ladle off about ½ to ¾ cup of the braising liquid, and strain it into a small saucepan or frying pan. Set over high heat and reduce by at least half to a syrup, 10 to 15 minutes.

To serve, remove the chicken from the braising liquid and let all the juices drain in the pot. Place on a cutting board. You can break the bird down into pieces as you would for roast chicken, but for an authentic presentation, you’ll want to slice it into bite-sized pieces straight through the bone. A sharp cleaver is good for this, but mine is packed away so I usually do it with a good chef’s knife. It’s easier than you think, and often just requires a firm tap on the blade with a closed fist to cut through the bone. The leg and thigh bones are the toughest to cut through but you’ll get the hang of it. Transfer the pieces in their proper arrangement for each part of the thicken to a serving platter with a rim to catch any liquid and brush the chicken skin and meat with the reduced braising liquid syrup so it glistens. Serve any remaining syrup on the side.

Don’t forget to strain the braising liquid into a quart container and refrigerate until the next time you make soy sauce chicken. Then, just reheat it to a boil, add the chicken halves, and simmer according to the recipe. After five or so braises, you might consider adding a few of the aromatics to the braise to further intensify the flavor.

A Few Personal Notes on Ingredients

The distinct flavor soy sauce chicken comes from a combination of a number of ingredients that are typical to the dish. If you can find them all, great, but if not, I recommend some viable substitutions below.

Chicken

It’s important to have a good chicken. I know most people think all chickens are the same. This is not true. It is also not true that all expensive, heirloom, pasture-raised chickens are good. One of the unexpected benefits of spending time in Ithaca is finding Just a Few Acres Farm at the Ithaca Farmer’s Market. Their fresh-killed, pasture-raised chickens are plump, meaty, and flavorful. I remark on their quality whenever I eat it, causing Nate to roll his eyes at this point. I keep bringing them back to the city with us. Find a good chicken near you. If you can’t find one in your area, a friend recommended Jidori to me as a source, and their chickens, available in a few different qualities, are indeed very fine. Shipping is expensive, but they have occasional sales.

Note that I almost always find whole chickens preferable to parts. I rather break them down myself. But you can do this dish with a few thighs, some breasts (only on the bone and with the skin), or what have you. Keeping the braising liquid, as advised, makes it especially easy to whip up a little soy sauce chicken for one or two.

Shaoxing Wine or Rose Wine

I had never heard of rose wine (muy kwe lu or mei gui lu jiu) until I started doing some research into soy sauce chicken recipes while back and then I found the very one pictured in one of my favorite Chinatown grocery stores. You can use Shoaxing wine, which is more common, and which everyone who does any Chinese cooking should have on hand all the time, anyway. In a pinch I’ve used gin, which I was a trick I learned from a Chinese cook many years ago, and which works well, indeed.

Cassia

Cassia is commonly sold as cinnamon, though it is technically something else. Chinese recipes that call for cinnamon generally want you to use cassia, which I think has a more savory flavor, less like cinnamon rolls. I find cassia sticks in Chinatown that look more like bark than other cinnamon and I use these for red cooking because I think the flavor complements the star anise, which dominates. I’ve also used these amazing cinnamon leaves sold by Burlap & Barrel. Use what you’ve got.

Soy Sauces

Like chickens, not all soy sauces are the same. They differ between culinary traditions (Chinese, Korean, Thai, Japanese, and others) as well as regionally. Quality can vary considerably from one brand to the next. I love the specialty Sichuan soy sauces carried by The Mala Market. But for this chicken, which requires a relatively large amount of the stuff, I choose a more common and less expensive brand, such as Kimlan, Pear River Bridge, or Koon Chun Sauce Factor. Light and dark soy sauces are distinct, the dark having a richer, molasses flavor that is typical of this style of cooking. If you don’t have it, use light, and add more dark brown sugar. A dribble of molasses wouldn’t hurt, either.

Rock Sugar and Honey

Typical of this style of cooking is the use of Chinese rock sugar, sometimes sold as sugar candy, that comes in a variety of colors ranging from clear to dark brown. Any will work here, as will regular sugar. I use some honey for additional flavor complexity, but you can use additional sugar, too. Korean rice syrup also works.

Dried Tangerine Peel

This is another common flavoring in Chinese food, especially red cooking. You can find it in Chinatown, but I make my own during citrus season by laying pieces of tangerine peel on a rack in the window to dry for a few days in the open air. The peels darken and shrivel up. I store them in a plastic bag until I need them. They will last for years. If you don’t have any, throw in some candied orange rind, or even a few strips of fresh orange zest.

What To Serve with Your Soy Sauce Chicken

Don’t feel compelled to create a Chinese banquet your first time out. Soy Sauce Chicken makes a great weekday meal with some steamed rice and greens. If you have the braising liquid on hand, you can cook a few thighs in 30 minutes (skimping on the marinating time, which I do from time to time).

Scallion Ginger Sauce

I almost always have some of Francis Lam’s ginger scallion sauce in the fridge, and it is a traditional and perfect accompaniment to this chicken. You add a dab to the meat before you put it in your mouth. I also like to use it as an ingredient in other Chinese dishes, a little flavor bomb. At first I made half the recipe, thinking a whole batch would be too much for the two of us. Now I make it all and it goes quickly.

Steamed Greens

As for greens, I always have big bags of Asian greens in my fridge to steam and eat simply with oyster sauce. I like gai lan (Chinese broccoli, with thickish stalks), yu choy (thinner than gai lan, often with yellow flowers), baby bok choy (white stem) or Shanghai bok choy (green stem), or choy sum (like long thin boy choy). Serious Eats has a great guide to Chinatown greens. Whichever green you choose, be sure to trim the ends and rinse them very well to remove the sand. To do so, place them in a large vessel of cold water, swirl them around, let them soak a while, then lift them out and repeat. To cook, I put a little water, less than an inch, on the bottom of a big pot or frying pan. (I’m conscious of minimizing water waste in my cooking these days.) Bring the pan to a boil, add the greens (they can still be wet), cover, and steam for 4 or 5 minutes, until the thickest stalks are tender. I like mine a little past al dente. Remove them with tongs to a platter with a rim (a lot of liquid will accumulate) and drizzle with oyster sauce. For me, there is only one acceptable brand of oyster sauce, Megachef Premium Oyster Flavored Sauce, from Thailand.