Issue #84: Perfect Basmati Rice

A Foolproof Technique, Plus Three Recipes for That Rice Once You Cook It

Greetings from Liberty of the Seas, a cruise ship at sea somewhere between Ft. Lauderdale and the Bahamas. I’m onboard for a Taoist Tai Chi® retreat and I’m sure next week’s newsletter will be inspired by something we eat on this ship. In the meantime, I wrote this week’s before we embarked. Because the Internet is spotty, I’m sending it a little earlier than usual.

Usually, I look back at what I cooked over the past few days to consider whether any recipes might be worth sharing. I’ve come to realize that sometimes I’m more focused on the main dishes than the staples and underlying techniques that make the meal. (There may be a lesson for all cooks in that observation.) That’s how I came to basmati rice, which finds its way to our table in many forms, but which I cook without giving it much thought. Several comments on the quality of my rice in person and on recent Instagram photos brought my attention to the rice pot. I hope you find this helpful.

Coincident to the topic of basmati, the new episode of my What’s Burning podcast that drops Wednesday features celebrated Indian chef Chintan Pandya, whose New York City restaurants, Adda, Semma, Dhamaka, Masalawala, and Rowdy Rooster have earned him accolades and awards from just about every food magazine, the New York Times, the James Beard Foundation and Michelin. Although I work closely with Chintan on occasion, I learned a lot in our conversation. Have a listen here. —Mitchell

Lately, I’ve been cooking a lot of Indian, Persian, and Middle Eastern food. There is tremendous variety within each category and many similarities among them, due in part to the ancient spice routes, I imagine. Aromatic rice is a common denominator.

I love rice in its many forms, particularly jasmine and basmati.

I once attended a fascinating conference on rice in South Carolina organized by the inimitable Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills. There, I learned that there are really only two main varieties of Oryza sativa, the most common rice; they are japonica and indica. Japonica is the line that produces the short-grain, starchy, sticky rices eaten with Chinese food, used for sushi, and stirred to make Italian risotto. Inidica is the longer, thinner, more proteinous and aromatic rice that gives us basmati. Jasmine rice is actually a short-grain japonica rice into which the aromatic gene from indica has been bred.

Anyway, it has dawned on me that over the weeks and months I’ve been writing this newsletter, I’ve given you many recipes for different dishes that I serve with basmati rice, while taking the rice for granted.

I grew up on Uncle Ben’s “converted” rice, a bland, soft, thoroughly uninteresting pre-cooked and processed rice product with a racist name and iconography to match that was a staple in my mother’s home. I’m not quite sure how marketers convinced suburban housewives of a certain era that some special treatment was needed to make rice that would hold it’s shape and that you could fluff with a fork. Perhaps that's where the offensive black stereotypes came in. But they did. It was a product of the times. (Btw, it is now called Ben’s Original.)

Part of growing up as a cook for me was realizing there were so many different varieties of rice, each with a different taste and texture, and each suited to its own array of dishes. Counting in my head, in my cupboard right now I think I have eight or nine different rices (not including rice flours and noodles).

Perhaps because of my mother, I used to find cooking rice intimidating. I could never quite remember the ratio of water to rice or the best technique to use from one batch to the next. Whenever anyone served me perfect rice, I would interrogate them about how it was made. For these reasons, I took to a rice cooker at an early age, a kitchen appliance I still love and admire because it pretty much makes cooking rice brainless. But although you can make just about any rice in a rice cooker, I find that some rices, especially basmati, are better made another way.

In fact, I don’t know where I first learned how to make basmati rice the way I’m going to share with you. I first wrote about it in my Kitchen Sense cookbook back in 2006, and to be honest, until recently, I had to consult my own book each time I made it because I was afraid I’d get it wrong. (I wasn’t kidding when I said cooking rice used to intimidate me.) But this method is quick (once the rice has been soaked), requires no measuring, and produces perfect basmati rice every time—virtually foolproof.

Basmati rice is delicious plain, as is. I can’t resist eating spoonfuls of it out of the pot. But there are also so many simple things you can do with it to perk it up a little. In addition to my master technique for rice, I’m going to give you three simple dishes to make with basmati. I find because basmati isn’t sticky like other japonica varieties, it is ideal for cold rice salads and other dishes, too.

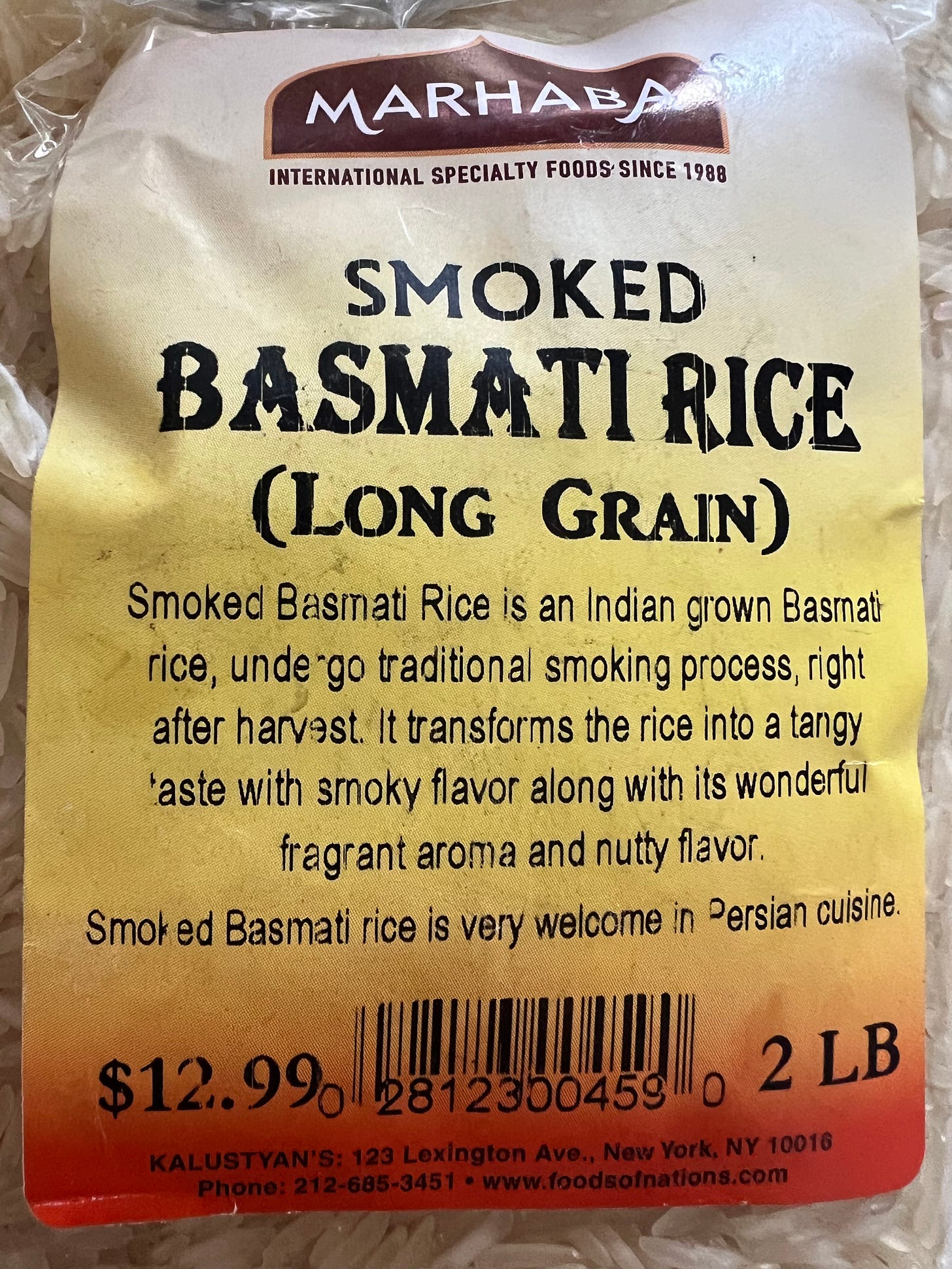

A word about which basmati to buy. Like any ingredient that has a long history in many different culinary traditions, there are many different qualities of basmati rice. I generally find that if you are in a good Indian or Middle Eastern market, the more expensive the basmati, the better. (This approach doesn't work in a generic, fancy gourmet market, where everything is overpriced.) The qualities you are looking for are long grains and aging. Yes, unlike the priciest japonica rices, the new harvest of which is highly prized, there is a premium placed on basmati that has been aged, up to two years or more. Aging basmati reduces the moisture content and increases the flavor. I recently splurged on a “super-quality,” “extra-long grain,” Dehraduni Indian basmati at Kalustyan’s and it was a revelation. I’m also a fan of a little known smoked basmati rice that Kalustyan’s carries, the slightly smokey flavor of which adds additional warmth and complexity to some dishes.

TECHNIQUE: Perfect Basmati Rice

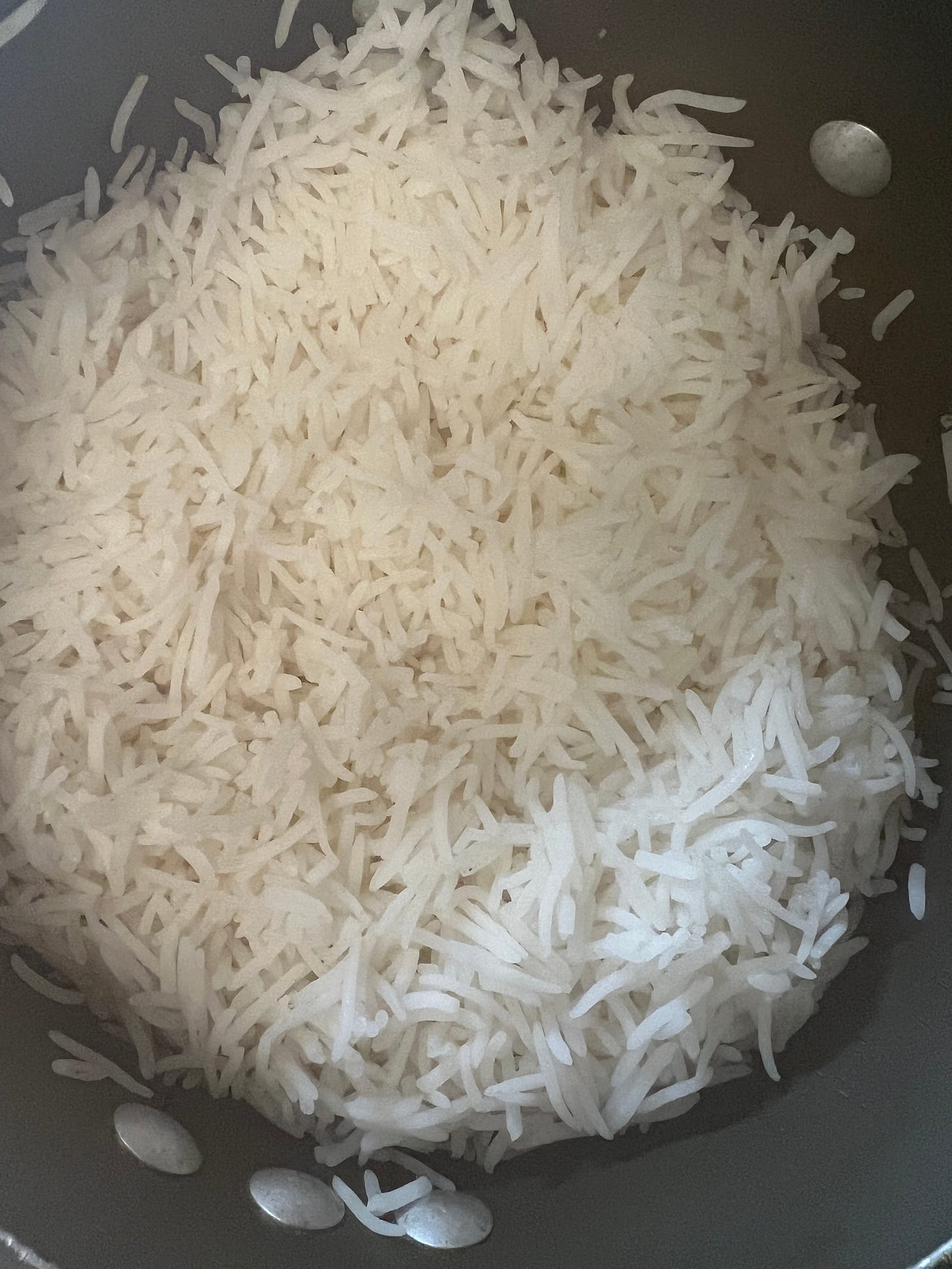

Place 1, 2 or 3 cups (or thereabouts) of basmati rice in an appropriately sized pot. You’ll want to have enough room for the rice to triple in volume. Cover the rice with cold water, swish around until the water is a little murky, then drain in a sieve or colander (with small holes). At this point and throughout you want to do everything you can not to break the long, delicate grains of rice. Return the rice to the pot. Cover with fresh cold water a couple of inches above the top of the rice and let soak for at least 30 minutes and up to 2 hours. Be sure an inch or so of water above the rice remains. If not, add more.

Once soaked, add a pinch of salt and place the pot on the stove over high heat. Bring to a boil, reduce the heat slightly to produce a gentle but persistent boil, and let cook for 5 minutes, no more (a little less is okay, especially if the rice has soaked longer than 30 minutes). Drain the rice well in the same sieve or colander you used before, return the rice to the pot, cover, set over the lowest heat on your burner, and allow the rice to steam/dry for 5 minutes. Turn off the heat, keeping the pot covered, and let sit for 15 minutes. Fluff with a fork, sneak a few spoonfuls, and serve.

RECIPE: Herbed Basmati Rice

Use whatever herbs you have in the fridge, but be sure you’ve got a variety. I’ve been using a lot of celery leaf as an herb lately (yes, just the leaves of celery), and their distinct flavor is particularly good in the mix for this dish. You can omit the seeds, if you wish. Use the master technique to cook the rice.

(Serves 6 to 8)

1 to 1 1/2 cups assorted chopped fresh herbs, such as parsley, cilantro, mint, dill, celery leaf, chives, and/or tarragon

1/4 cup assorted toasted seeds, such as pumpkin, sunflower, and/or sesame

4 or 5 cups just-cooked, warm basmati rice

Freshly ground black pepper

In a large bowl, combine the chopped herbs and toasted seeds. Add the warm rice, some freshly ground black pepper, and toss carefully with a rubber spatula to evenly distribute without breaking up the grains. Serve warm or at room temperature.

RECIPE: Bejewelled Basmati with Toasted Nuts and Dried Fruit

This dish was an accident. I set out to make a delicious Palestinian salad with herbs, dried fruit, and nuts from my friends’ Bonnie and Anna’s cookbook Don’t Worry, Just Cook. But after I cut up the fruit and chopped the nuts, I realized I didn’t have any herbs and was almost out of lettuce. So I tossed them into some cold basmati rice instead and added the honey lemon dressing. It was delicious and beautiful, the dried fruit sparkling like jewels. The dish benefits from a wide variety of dried fruit and nuts. In season, the pomegranate seeds add great flavor and texture and contribute to the jeweled appearance of the rice. Toasting the nuts a few minutes in a warm oven enhances their flavor. You could also add a bunch of chopped herbs (see recipe, above). Use the master technique to cook the rice. Sadly, I didn’t take a photo of this dish the few times I made it recently. You’ll just have to trust me that it’s beautiful and make it for yourself.

(Serves 6 to 8)

2 tablespoons olive oil

Juice of 1/2 lemon

1 teaspoon honey

1/2 to 1 cup assorted chopped dried fruit, such as raisins, cherries, apricots, dates, blueberries, and currants, in any combination (the more variety the better)

1/2 cup toasted mixed nuts, such as almonds, cashews, pecans, walnuts, pistachios, Brazil nuts, and/or macadamias, roughly chopped

1/4 cup fresh pomegranate seeds, optional

4 to 5 cups basmati rice, cooled

In a small bowl, combine the olive oil, lemon juice, and honey to make a dressing. In a large bowl, combine the dried fruit, nuts, and pomegranate seeds, if using. Add the rice to the large bowl, along with the dressing, and using a rubber spatula, toss carefully to distribute the ingredients without breaking the grains of rice. Serve at room temperature.

RECIPE: Golden Yogurt Rice

This is a colorful, delicious Indian rice that can be served warm, room temperature or cold. If you have the dals (Indian legumes) handy and have time to soak them, I would suggest you add them for both flavor and texture. But they can be left out without diminishing the deliciousness of this dish.

(Serves 6 to 8)

2 tablespoons urad dal (black gram lentils), optional

2 tablespoons chana dal, (skinned, split small chickpeas), optional

8 ounces (a scant 2 cups) basmati rice

2 tablespoons peanut or other vegetable oil

A generous 1/2 teaspoon black mustard seeds

12 to 16 fresh curry leaves

3 dried red chilies, split in half and seeded

A generous 1/4 teaspoon ground turmeric

Pinch asafoetida or onion powder

2 cups thick plain yogurt

Pinch salt

If using the dals, combine both in a small bowl, cover with cold water, and soak for 4 to 6 hours or overnight. Drain well and then pat dry with paper towel to drain further. Cook the rice according to the technique above.

In a small saucepan or frying pan, heat the oil over medium-high heat. Add the mustard seeds, swirl around a little, and cook until they begin to pop. Add the curry leaves, chilies, and the drained dals, if using, and cook 3 or 4 minutes, until you can see evidence of slight browning and softening. Add the turmeric and asafoetida, stir another 30 seconds or so, and take off the heat.

If not using the dals, once the mustard seeds pop, add the curry leaves, chilis, turmeric and asafoetida, and cook for under a minute until the spices are fragrant. Remove from the heat.

Place the yogurt in a large bowl. Add the cooked spices and dals, if using, scraping every last bit out of the pan, and a pinch of salt, and stir well. The yogurt should take on a lovey golden color. Stir in the cooked rice using a rubber spatula, being careful not to break up the grains. Cover and let sit at room temperature for at least 15 minutes to absorb the yogurt before serving.

Beautiful! Thank you, Mitchell. Have you ever noticed how ALL (never say all, maybe almost all) traditional directions for cooking rice, from China to India to South Carolina, suggest covering the rice at the end, removing it from the heat, and letting it sit quietly for 5 or 10 minutes before serving? Which is what you're doing here too.